In his first monetary policy, unveiled on August 17, as governor of Nepal Rastra Bank, Maha Prasad Adhikari, rolled out an expansionary policy that aims to provide regulatory as well as immediate relief to struggling businesses and households from pending loan obligations. The healthcare and economic shocks owing to COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns to contain its spread have been unprecedently disruptive. Given the extended period of lockdowns, supplies disruption and subdued aggregate demand, economic growth in fiscal 2019/20 is projected to be much lower than 2.3% estimated by Central Bureau of Statistics before the pandemic. The shortage of goods and services has increased inflationary pressures, and lending interest rates have remained in double-digits. The acute cash flow problems faced by businesses, and either layoffs or reduced working hours faced by individuals have increased the risk of a liquidity crisis morphing into a solvency crisis.

Against this backdrop, the monetary policy for 2020/21 aims to achieve the ambitious 7 percent economic growth target set by the government, maintain adequate liquidity, limit inflation to 7 percent, encourage merger of banks and financial institutions, enhance access to finance, and promote reliable digital transactions. The conventional monetary policy tools as well as macroprudential policies have been much more accommodative than what we have seen after the catastrophic earthquakes in 2015. The private sector and banking associations have welcomed the measures outlined in the policy.

Monetary instruments

Among the targets for 2020/21, the central bank wants to limit average inflation to 7%, ensure foreign exchange reserves adequate to cover 7 months of goods and services import, ensure adequate liquidity to facilitate economic recovery and to achieve 7% growth target, 18% growth in money supply, and credit growth to private sector of 20%.

Since we have fixed our exchange rate with the Indian rupee, Nepal Rastra Bank cannot independently control inflation. Furthermore, supplies side constraints such as a lack of adequate and reliable infrastructure (electricity, road network, and irrigation among others), fuel prices, and market imperfections in the form of cartels or syndicates also affect inflation. That said, NRB can influence credit flows to sectors that are seeing sharp rises in prices. By setting inflation target of 7% NRB has adopted an accommodative monetary policy stance as it seeks to facilitate adequate liquidity and credit flows to sectors affected by COVID-19 pandemic.

To achieve these targets, the central bank is planning to use a number of monetary instruments at its disposal. Although controlling inflation is not fully within the domain of Nepal Rastra Bank, thanks to the fixed exchange rate regime, it nevertheless has accommodated a higher inflation target than last fiscal by rolling an expansionary monetary policy. For instance, it has reduced policy repo rate, which is the rate of interest charged by NRB on the repurchase of government securities, by 50 basis points to 3 percent. This essentially increases liquidity as BFIs can now borrow money at a lower rate from NRB by selling government securities they hold. NRB also uses repo rate to maintain interest rates within the interest rate corridor, which is aimed at reducing interest rate volatility. Similarly, it has reduced term deposit rate, which is the lower bound of interest rate corridor, by 100 basis points to 1 percent. This will discourage BFIs to deposit extra money at the central bank because the rate of return will be even lower. It has also committed to allow long-term repo facility if required as current repo operations are limited to two weeks. In March 2020, NRB had already reduced cash reserve ratio and bank rate by 100 basis points to 3 percent and 5 percent respectively, and lowered policy repo rate by 100 basis points. These measures are aimed at increasing liquidity and to lower interest rates.

In addition to these traditional monetary policy instruments, the central bank has also provided regulatory relief by tweaking macroprudential policies, which are designed to mitigate system-wise risk and to reduce asset-liability mismatches. For instance, it suspended two percent countercyclical buffer requirement, which commercial banks have been maintaining in addition to minimum 10% capital adequacy ratio. The additional buffer is imposed during normal times to lower systemic risk in case of a sudden deterioration in balance sheets. It has tweaked loan classification by allowing credit extended to healthcare sector to be counted as priority sector lending and waived off fees on online transactions. It has increased credit-to-core capital cum deposit (CCD) ratio to 85 percent from 80 percent till 2020/21.

NRB has also extended moratorium on loan payments and allowed for restructuring as well as rescheduling of loans provided to COVID-19 affected sectors. Furthermore, the central bank has limited dividend payments and extended deadline for issuing debentures or corporate bonds equivalent to at least 25 percent of paid-up capital. Soon it will introduce a loan classification provision whereby good loans affected by COVID-19 may not be required to be classified as bad loans. For some loans that are not repaid by 2020/21, loan loss provision could be just 5 percent.

Similarly, it has capped loan-to-value ratio for residential home loan at 60%. For real estate, it has maintained the earlier 40% cap in Kathmandu valley and 50% outside of Kathmandu valley. For margin lending, it has increased the cap to 70% from 65%, and the valuation is to be based on the average value in the last 120 days, down from earlier 180 days. BFIs can also extend an additional working capital loan equivalent to 20% of the value as of April 2020.

Directed lending

Another important aspect of the monetary policy is its emphasis on directed lending, especially to agriculture, energy, tourism, and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). The central bank has mandated commercial banks to lend at least 15%, up from 10%, to agriculture sector by 2022/23. It has also proposed to transform Agriculture Development Bank Limited as a lead bank for credit to agriculture sector. ADBL is allowed to issue agricultural bond, which commercial banks can purchase to fulfill their own credit requirement to the sector. It has also proposed issuing ‘kisan credit card’ through ADBL, and to simplify existing credit swap facility among BFIs pertaining to agricultural loans.

Meanwhile, commercial banks will have to lend at least 10%, up from 5%, to energy sector by 2023/24. Commercial banks with experience in energy sector lending are allowed to issue energy bond, which will help to raise long-term capital to finance hydroelectricity projects. For export-oriented hydroelectricity projects and reservoir type projects, BFIs will have to extend loans at rate that is just one percentage point higher than the base rate. Similarly, the NRB has given priority to travel and tourism sector in working capital and subsidized loans (at 5% interest), and in refinancing facility. Commercial banks are required to lend (each loan less than NRs 10 million) at least 15% of total loans to MSMEs by 2023/24.

Total directed lending has shot up to 40%, up from 25%, for commercial banks. Development banks and finance companies are mandated to lend at least 20% and 15%, respectively, to agriculture, MSMEs, energy and tourism sectors by 2023/24.

Refinancing facility

The NRB has committed to increase refinancing facility by 5-fold to support economic recovery. Of the total refinancing pool offered by NRB, 20% will be offered as per the individual evaluation of clients, 70% through BFIs, and 10% through microcredit institutions. Depending on the nature of business and the effect of COVID-19 pandemic, refinancing loans attract interest between 2% and 5%. For those refinancing loans offered by BFIs, micro and small enterprises can avail a maximum Rs 1.5 million, and the rest can avail between Rs 50 million and Rs 200 million.

Merger and acquisition

The NRB has continued its merger and acquisition policy by providing additional incentives. For instance, BFIs merger by FY2021 will see 0.5 percentage point lower CRR requirement and one percentage point lower capital adequacy ratio, increase in institutional deposits thresholds by 10 percentage points, and lower cooling off period for executive board members and high-level staff, among others.

Implementation challenges

These policies are appropriate given the scale of the crisis we are facing. However, as in the past, the main challenge lies in fully and timely implementing the regulatory relief and concessions. The central bank will also have to be ready to deal with some of the unintended consequences as a result of the policies it has adopted.

First, monetary policy has addressed the supply of credit part by facilitating availability of liquidity and taking policy measures to keep interest rates down. However, this does not mean all of it will be taken up. The demand for loans for business recovery is contingent on the overall investment climate and growth prospects. Not many businesses will take additional loans just to keep employees in payroll and to pay cost rent and operations costs when there are already substantial losses piled up since the lockdown started. Soon liquidity crisis faced by firms and households may turn into solvency crisis, which will increase the share of bad assets of BFIs and eventually squeeze credit flow. The uncertainty over the likely path of economic recovery further complicates the matter. At this stage, the government should have guaranteed additional working capital loans offered through the banking sector to COVID-19 affected businesses. This would have increased demand for credit and also prevented business closures and layoffs.

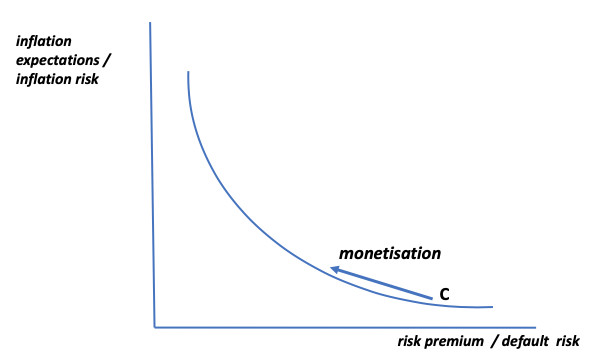

Second, BFIs are generally risk averse amidst lack of improvement in investment climate, growth prospects and governance. They may not be willing to extend credit to new or existing borrowers without being confident about timely repayment. Consequently, the additional liquidity facilitated by NRB may end up back in its own vault because BFIs will see it safer to park funds there even if the rate of return is much lower. BFIs could also purchase government securities and bonds if they are unwilling to increase lending to borrowers in fear of default risk. It will drive down the interest on government security and bonds.

Third, extending moratorium on payments simply postpones the inevitable, if economic activities do not pick up: a rise in non-performing assets. Subdued business activities and tepid cash flows, and lower income of households due to job losses might lead to unserviceable loans, which eventually are classified as non-performing assets. Despite the commitment by NRB to reschedule and restructure troubled loans, the risk is still there. Note that concerns have been raised repeatedly by International Monetary Fund about the low level of non-performing assets due to the ever-greening and at times imprecise classification of risky assets. Higher levels of non-performing assets in the banking sector pose systemic risk, substantially lower credit growth, and affect economic growth. Perhaps, it is also a good time to deliberate with Ministry of Finance on a potential bad assets management strategy in case things do not turn as expected.

Fourth, the large refinancing facility may not be fully utilized if the banks and financial institutions do not see viable investment projects or creditworthy borrowers. Refinancing facility is offered by central bank but its eventual execution is through the banks and financial institutions. The past refinancing pool offered to households for reconstruction of residential houses destroyed by the earthquake have not been utilized fully. The central bank had offered Rs 2.5 million for households in Kathmandu valley and Rs 1.5 million for households outside the valley. The BFIs could avail the refinancing facility at zero percent interest rate and offer it to clients by levying a maximum two percent interest (excluding third party costs such as insurance, collateral evaluation, loan security fund, etc) for period between 5 to 10 years. Refinancing facility details will be clear after the central bank releases standard operating procedures to execute the policy.

Fifth, the aggressive push on directed lending— constituting over 40 percent of total loans, up from 25 percent last fiscal— could increase banking sector inefficiencies if proper due diligence is not followed through when extending credit to such sectors. Forcing BFIs to extend credit to particular sectors if they do not have expertise in evaluating soundness of projects is not a good strategy. It invites political interference and fosters moral hazard behavior. For instance, what happens if BFIs are forced to meet the mandatory share of lending to energy sector if hydro projects fail to finalize a viable power purchase agreement with the off-taker? Similarly, what happens if farmers fail to pay debt on time (in the past, the government waived them off with taxpayer funded fiscal rescue). Half-baked and poorly governed directed lending might further exacerbate asset-liability mismatches. Note that NRB started priority sector lending for commercial banks in 1974. It was phased out in 2005 as a part of financial sector reform program as banking sector inefficiencies and political interference bloated non-performing assets as well as misuse of priority sector lending. However, it was again reintroduced in 2012 with 10% minimum lending to agriculture and energy sectors. It was increased to 12% in 2014 and then again to 25% in 2018. Priority sector lending includes credit to agriculture, tourism, MSMEs, pharmaceutical, cement, garment and tourism.

Sixth, the current incentives for merger may be insufficient as it is primarily held back by differences in ownership and appointments after merger. Nepal has too may BFIs for the size of its economy and there is cut-throat competition without much innovation to attract deposits and to extend loans. In the past, this has led to deterioration in quality of loan approvals, asset-liability mismatches, and sectoral bubbles, which eventually led to a financial crisis in 2011 as real estate and housing bubbles burst. Subsequently, the NRB imposed a cap on lending to the sector.

Seventh, the plan to transform ADBL, a commercial bank, into a lead bank for agricultural sector may need to thought out well before execution. Initially, it was founded as a separate development bank catering to the agricultural sector, especially in rural areas. After the endorsement of Bank and Financial Institutions Act (BAFIA) in 2005, it operated as a public limited company licensed as a ‘class A’ financial institution by NRB. As a part of rural finance sector development cluster program, they government reduced its share in ADBL to 51% through divestment, and restructured its capital and management (including voluntary retirement of excess staff). The main problem in ADBL before its restructuring was political interference, management inefficiencies, and politically-backed loan or subsidy schemes that government pushed through it. Without clear guidelines on absorbing any risk of default and identification as well as targeting of actual beneficiaries, the new ‘kisan credit card’ may actually increase ADBL’s burden. This kind of credit scheme is used to help farmers meet immediate operational or capital needs such as purchase of fertilizers and seeds before sowing, and tractor or motorcycle after the harvest. After disbursing credit to farmers, it is difficult to monitor if they used it as they said they will during the application process.