This is adapted from Macroeconomic Update, August 2015, Vol.3, No.2 (executive summary here, and FY2016 growth and inflation outlook here). It presents is the composition of Nepal’s outstanding internal and external debt. The Macroeconomic Update includes FY2015 update on real, fiscal, monetary and external sector, and growth and inflation outlook for FY2016. It provides a comprehensive macroeconomic assessment, including fiscal sustainability, after the April 25 earthquake.

I. Expenditure Performance

1. The sluggish expenditure in the first three quarters and damages caused by the earthquake in the last quarter of FY2015 significantly affected public expenditure. The budget execution delays, and long-running procedural as well as procurement hassles constrained absorptive capacities[1], resulting in slower capital spending than previous years. After the April earthquake, the institutional and bureaucratic mechanism derailed for about two weeks and then it resumed with a singular focus on rescue and relief operations. This virtually stalled the capital spending related procedural approval, procurement execution, and implementation not only in the earthquake-affected areas, but throughout the country. The estimated actual capital spending was 69.9% of planned capital expenditure in FY2015, lower than the 78.4% achieved in FY2014. Meanwhile, actual recurrent spending was 84.4% of planned recurrent expenditure, marginally lower than the 85.9% in FY2014 (Figure 1). Overall expenditure grew by 13.0%, with recurrent and capital spending growth at 11.0% and 22.3%, respectively— lower than the growth rates in FY2014 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Absorption capacity (% of planned expenditure)

Figure 2: Growth rate of total, recurrent and capital expenditures (% change)

2. Within recurrent expenditures, compensation of employees increased by 4.1%, grants to local bodies and subsidies[2] by 10.4%, use of goods and services[3] by 8.2% and social security by 48.6%. Overall, recurrent expenditures are estimated to be 15.9% of GDP, marginally higher than 15.6% of GDP in FY2014 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Recurrent expenditures (% of GDP)

3. Capital spending continued to be sluggish, reaching just 3.8% of GDP against 5.5% of GDP planned for FY2015 (Figure 4). Apart from the slowdown caused by the earthquake in the last quarter, the time when most of the capital spending happens, of FY2015, other persistent factors impeding capital spending are: (i) lack of project readiness, in terms of timely preparatory activities such as detailed project design, land acquisition, establishment of project management offices and required personnel, and procurement plans; (ii) delays in project approval and budget release; (iii) delays in procurement related processes; and (iv) overall weak project planning and implementation capacity[4]. The damage caused by the earthquake in addition to the large investment needed to close the infrastructure deficit has meant that Nepal needs to drastically enhance its capital budget execution performance. Else, the foundations for graduation from LDC category to a developing country status by 2022[5] and the overarching goal to become a middle income country by 2030 will continue to remain weak.

Figure 4: Total, recurrent and capital expenditures (% of GDP)

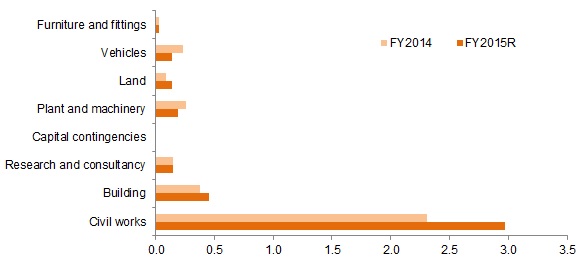

4. Within capital expenditure although vehicle purchase declined by 31.8%, all other components registered robust growth. But still actual capital spending fell far short of the planned capital spending. Spending on building construction, plant and machinery, and research and consultancy grew by over 90%. Building related capital spending grew by a whopping 286.8%, which could partly be attributed to the low base effect. The expenditure for civil works increased by 113.5%, reflecting slightly better performance than previous years but still requiring further enhancement. Except for civil works— which was 2.3% of GDP, the same as in FY2012 and FY2013— none of the eight sub-categories within capital expenditures was above 1.0% of GDP (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Capital expenditures (% of GDP)

5. As in the previous years, FY2015 saw bunching of spending, especially capital spending, towards the last quarter. Almost one-fourth of actual total public expenditure was done in the last month and 43.9% in the last three months. Of the actual capital spending, 37.8% was spent in the last month and 61.2% in the last three months (Figure 6). This pattern of spending is not much different from previous years, irrespective of the timeliness of issuance of budget. It raises concerns about not only the absorptive capacity, but also the structural issues concerning budget execution.

Figure 6: Monthly spending in FY2015, NRs billion

6. The ballooning recurrent expenditure needs to be rationalized by cutting down subsidies; improving the quality of spending, including operations and maintenance of assets created; weeding out unproductive projects; and reducing the number of priority projects so that more focus is accorded to the strategically important ones. Planning, allocation, delivery, monitoring and evaluation of public sector expenditure must be efficient and productivity-oriented. The urgency also comes from the fact that tax revenue mobilization and its growth rate are marginally higher than recurrent expenditure and its growth rate. Rationalization of recurrent spending will create more fiscal space to boost allocations for capital spending, which needs to be drastically ramped up to create the physical and social infrastructure foundations to accelerate short-term growth and to sustain long-term growth, resulting in an accelerated, high and inclusive growth process.

II. Revenue Performance

7. Total revenue grew by 13.8%, much lower than 20.5% growth in FY2014, reaching NRs405.8 billion (19.1% of GDP). It is lower than the budget target of NRs422.9 billion as the slowdown in economic activities and imports following the earthquake in April hit revenue mobilization. While non-tax revenue grew by 13.0% as opposed to an increase by 20.1% in FY2015, tax revenue growth slowed down to 13.9% from 20.5% in FY2014. Tax revenue and total revenue growth rates have been continuously decreasing since FY2013. As a share of GDP, tax revenue mobilization has improved significantly, reaching 16.8% in FY2015, up from 9.8% of GDP in FY2007 (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Tax and non-tax revenue (% of GDP)

8. The continuous reforms in revenue administration, broadening of the tax base, and the higher import bill (mostly financed by remittance income) resulted in robust revenue performance over the last decade. Some of the notable reforms undertaken in recent years include: (i) information and communication technology based tax returns filing and payments systems; (ii) establishment of a data link with the Company Registrar’s Office to enhance tax compliance[6]; (iii) measures to reduce tax compliance costs; (iv) strengthening of tax monitoring and audit systems; (v) measures to widen the tax net for various tax categories; and (vi) implementation of the Any Branch Banking System (ABBS) for large tax payers.

9. Revenue mobilization from major sources decelerated in FY2015. The growth rates of value added tax (VAT), income tax, customs and excise duty were lower than in FY2015. They grew by 11.3%, 14.1%, 10.1% and 17.9%, respectively. Meanwhile, land registration fee, vehicle tax and health service tax grew by 41.3%, 26.9% and 31.7%, respectively— higher than the growth rates in the previous year (Figure 8). The deceleration in the major sources of revenue is attributed to the economic and imports slowdown following the earthquake. The acceleration in vehicle tax and land registration fee mobilization is due to the higher import of vehicles and land transactions, respectively, in the first three quarters of FY2015. The slower non-tax revenue growth is attributed to the decrease in interest and dividend paid by some public enterprises. Overall, VAT contributed the largest (27.7%) to total revenue mobilization, followed by income tax (22.0%), customs (18.4%), and excise duty (13.2%) (Figure 9). Taxes on consumption and imported goods, which are largely financed by remittance income, constitute a lion’s share of total tax revenue mobilization—around 70%. Furthermore, import-based revenues (custom duties, VAT, and excise on imports only) account for about 45% of total revenue.

Figure 8: Revenue growth (% change)

Figure 9: Composition of total revenue in FY2015

III. Fiscal Balance

10. The lower than expected revenue mobilization along with the disappointing expenditure performance resulted in a fiscal deficit[7] equivalent to about 0.2% of GDP in FY2015 (Figure 10). Though this is better than the fiscal surplus equivalent to 0.7% of GDP in FY2013 and 0.6% of GDP FY2014, it is still lower than the medium-term average fiscal deficit of about 2.2% of GDP. For a low-income country with a large financing need to bridge the infrastructure deficit, particularly in hydropower and transport, running a modest fiscal deficit without jeopardizing fiscal sustainability is desirable. Nepal faces an estimated infrastructure financing gap of between 8-12% of GDP until 2020. The damage wrought by the earthquake and subsequent aftershocks has necessitated the need to ramp up even more productivity-enhancing public spending in physical and social infrastructures.

Figure 10: Fiscal indicators (% of GDP)

11. The total net borrowing amounted to just NRs2.9 billion in FY2015 (0.1% of GDP). Net external borrowing was NRs8 billion, but net internal borrowing was a negative NRs5 billion. The amount of foreign grants is continuously declining since FY2011, when it was 3.4% of GDP against 1.8% of GDP in FY2015, indicating the slow disbursement in projects funded with foreign assistance. This is not ideal given the large investment required not only in infrastructure, education and health sectors, but also in capacity building of public institutions. Furthermore, Nepal has been running a primary surplus since FY2012, meaning that fiscal balance before interest payment on public debt is positive (Figure 11). Combined with the low and declining outstanding public debt, it indicates that the government has ample fiscal space for now to expand productivity-enhancing public capital investment without jeopardizing fiscal sustainability. Box 3 includes further analysis on fiscal sustainability.

Figure 11: Primary and fiscal balance (% of GDP)

IV. Public Debt

12. Nepal’s overall outstanding public debt (external and domestic) has been steadily declining, reaching an estimated 25.6% of GDP in FY2015 (Figure 12). Total external debt decreased to 16.1% of GDP in FY2015 from 17.9% of GDP in FY2014. Similarly, total domestic debt declined to 9.5% of GDP from 10.6% of GDP in FY2014, reflecting the lower than targeted domestic borrowing as a result of the wide gap between actual and planned expenditure. External debt service payments stands at around 8.1% of exports of goods and non-factor services. The declining stock of public debt and debt service payments generally indicate prudent fiscal and public debt management. Nepal’s external debt is mostly on concessional terms and faces low debt distress as per the latest debt sustainability analysis. Box 1 provides further insight on the composition of Nepal’s outstanding public debt.

Figure: 12: Public debt (% of GDP)

V. Public Enterprises

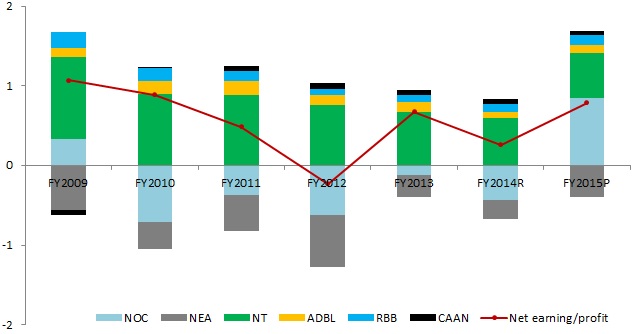

13. The overall performance of public enterprises (PEs) worsened in FY2014 as a result of large losses incurred by Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) and Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA). The continued mismatch between international price of oil and domestic retail price led to the huge losses of NOC. Similarly, the mismatch between per unit production cost of electricity and per unit selling price resulted in large loss of NEA. However, in FY2015 the net profit of public enterprises is expected to increase drastically, largely due to the huge profit earned by NOC and stable profit of Nepal Telecom (Figure 13). Of the 37 PEs, 15 are expected to make losses in FY2015. As a result of the automatic price adjustment mechanism followed by NOC and continued low international oil prices, including that of LPG cooking gas, NOC is expected to post net profit of NRs18.0 billon (0.85% of GDP) after five years of continued losses. NEA’s losses are expected to increase by twofold to NRs8.5 billion (0.4% of GDP) as the wedge between production and retail price widens. [8] Nepal Telecom is expected to post a marginal increase in profit, reaching NRs11.9 billion (0.6% of GDP).

Figure 13: Net earnings of select public enterprises (% of GDP)

14.. The cumulative liabilities of PEs decreased from 2.5% of GDP in FY2013 to 1.8% of GDP in FY2014 as a result of the decline in both unfunded and contingent liabilities. The unfunded liabilities (salary, pension, social security contribution, health care, and recurrent costs, among others, that the PEs cannot finance themselves) had increased steadily from 1.0% of GDP in FY2009 to 1.6% of GDP in FY2013 and marginally declined to 1.4% of GDP in FY2014. A major contributor to the rise in unfunded liabilities is the hike in salary and allowances in the public sector. Meanwhile, contingent liabilities (state guarantees of loans, defaults of PEs, and clean-up liabilities of privatized PEs, among others) increased in FY2013 after a steady decline in the past four years, but again declined in FY2014. It declined from 0.9% of GDP in FY2013 to 0.5% of GDP in FY2014 (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Unfunded and contingent liabilities (% of GDP)

15.. Either privatization or liquidation of loss making PEs needs to be accelerated to reduce the budget drain. The weak financial position of PEs has led to large unfunded liabilities, especially for pension and other related retirement benefits, which could ultimately become the government’s liabilities. It may be noted that due to the lack of accurate and updated data, the contingent liability of PEs presented here are at best conservative estimates. It is likely that the government is exposed to much higher level of liabilities. In this regard, fiscal and macroeconomic stability could potentially be subject to significant risks. Continuing the adjustment of electricity tariffs and automatic adjustment of fuel prices to reflect the true cost of production will help to lower the losses and liabilities.

[1] Absorptive capacity generally refers to the skills mastered by bureaucracy, state of infrastructure, and quality of institutions.

[2] Subsidies include direct subsidies to non-financial public corporations and private enterprises only. Actual direct and indirect subsidies are much higher. This does not include subsidies for chemical and organic fertilizer, micro-hydropower projects, transportation subsidy for seed and fertilizer supply, and interest subsidies to farmers groups and cooperatives, among others.

[3] Use of goods and services consists of (i) rent & services; (ii) operation and maintenance of capital assets; (iii) office materials and services; (iv) consultancy and other services fee; (v) program expenses; (vi) monitoring, evaluation and travel expenses; (vii) recurrent contingencies; and (viii) miscellaneous.

[4] The Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority’s (CIAA) pro-active monitoring of corruption in bureaucracy has also delayed decision making, especially those related to procurement.

[5] For a detailed analysis on prospects for Nepal’s graduation to a developing country status by 2022, see: ADB. August 2013. Macroeconomic Update. Vol.1, No.2, Manila: Asian Development Bank.

[6] The cost of collection per NRs1,000 decreased from NRs16.4 in FY2007 to NRs12.7 in FY2011.

[7] Fiscal balance is computed as expenditures (including net lending) minus revenue (including grants). However, normal fiscal balance (revenue minus expenditure and net financing) was a surplus equivalent to 1.3% of GDP.

[8] The high losses of NEA are also attributed to the rising electricity import, which is sold at suppressed rates, from India, and the still large provisioning for pension and gratuity of employees. The average electricity import price is NRs8.4 per unit, but the retail price is NRs8.04 per unit. Nepal imports around 250 MW of electricity during the dry season.