In VoxEU column, Jean-Pierre Landau argues that low interest rate and inflation rate create a conducive policy space for financing public expenditures in response to the COVID-19 shock. This is an optimal policy mix given the very low and stable inflation expectations. However, for this to be sustainable, central bank independence must be respected and reinforced. Monetizing government debt involves taking on future risks. For instance, financing instruments such as debt and money creation entail default risk and inflation risk, respectively. The process of monetizing debt involves managing the trade-offs between the two risks.

He states that post-COVID-19 monetary and financial landscape is characterized by: (i) high level of public debt in all countries; (ii) very large balance sheets of central banks; and (iii) a strong and immediate link between debt and monetary policy as a large part of government debt is held by central banks themselves.

Together, low interest rates and low inflation create, prima facie, a large policy space. It can be exploited to absorb the COVID-19 shock on public finances without fear of destabilising the economy. That space looks even larger if, in the years to come, central banks allow themselves to slightly overshoot their mid-range target of 2% inflation, to compensate for years of undershooting.

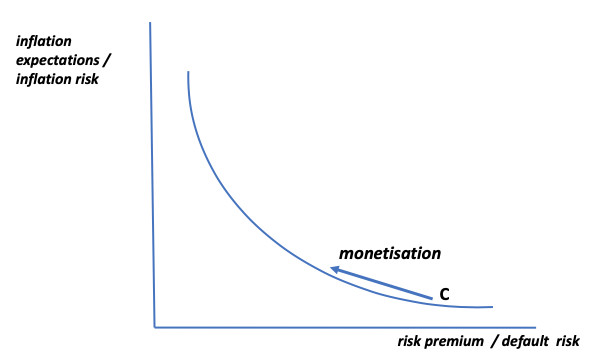

[...]At the moment, monetary policy operates through the purchase of government bonds. It changes the structure of the liabilities of the consolidated government, but not its size. It essentially amounts to transforming one form of liability into another. Doing so, it simply substitutes one form of risk to another. In the current policy environment, ‘monetisation’ is just a transformation of risks: from a credit and funding risk to an inflation risk.

[...]The curve moves up with the amount of financing that is needed. It moves down and left when growth expectations improve (as risk premium get smaller). Remarkably, it also moves left and down (and the slope decreases) if inflation expectations are lower or are better anchored (a sign of the credibility of the monetary authority). For given financing needs, monetisation is just a leftward move along the curve.

It seems safe to assume that most advanced economies are today positioned on the right part of the curve (around point C). There is an apparent sensitivity of risk premia to any news on debt. On the other hand, inflation expectations have not yet reacted to the monetary policy impulse that results from the expansion of central banks' balance sheets. If true, it is hard to escape the conclusion that current policies are close to optimal. In a rare moment of perfect fiscal - monetary coordination, governments are issuing bonds and central banks are buying government bonds and issuing money. Contrary to 2008–09, a large part of these purchases result in the creation of broad money in the hands of the general public (Lane 2020). Governments have the ability to lock in very low interest rates while central banks can expand their balance sheets without fear of missing their inflation objectives and mandates.

[...]In the post-COVID-19 environment, interactions between public debt and monetary policy will become more immediate and more intense. Fiscal and monetary authorities will have to pay greater attention to what the other is doing. There may be periods, as the one we are now going through, where close coordination will be appropriate and necessary. But conflicts may emerge in the future and the situation must be managed with that perspective in mind.

[...]In modern economies, inflation is mainly driven by expectations of future actions by the central banks. In a conventional environment, independence is meant to solve the time inconsistency problem by removing any incentive for the monetary authority to create an inflation surprise. Today, in an environment where high public debt interacts with a large monetary balance sheets, the justification for independence is more basic, even brutal: to protect the ability of the central bank to act in all circumstances.

The expectations that matter are not those relating to central banks' intentions, but those that concern the institutional environment in which they will operate. For inflation expectations to be durably stable, there must be no doubt that central banks will be in a position to raise interest rates should inflation pressures materialise, whatever fiscal (and public debt) situation exists at the time.