Inflation rate in Nepal reached double-digit for three consecutive years now and is now just above 9 percent. What are sources of inflation in Nepal? Is it following Indian price level? Is it being affected by demand side or supply side or both? How much is it affected by food prices? How much traction M2 (money supply) has on inflation in Nepal? In order to bring down the persistently high and sticky price level, policymakers need to first know the sources of inflation and then devise policies accordingly. The IMF recently published a study that looks into the sources of inflation in Nepal.

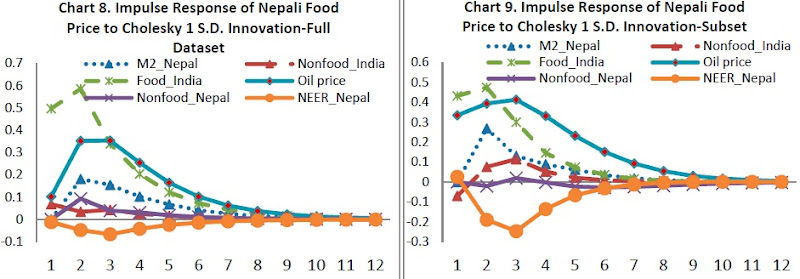

Using a VAR model to estimate the impact of external spillovers from India, international oil prices, nominal effective exchange rate, and domestic monetary factors, the study finds that inflation (both food and non-food) in Nepal is mainly driven by inflation in India and movements of international oil prices. These two factors account for more than one-third of the variability in domestic inflation. Since inflation in Nepal have been historically following inflation in India but not after 2007/08, the analysis uses two datasets: full dataset ranging from 2001 to 2011 and a sub dataset ranging from 2007 to 2011. The latter dataset shows that inflation in Nepal is deviating from India’s inflation and is becoming more responsive to oil prices. Note that Nepal has open border and pegged its currency with India.

Overall inflation

- Monetary factors matter more for nonfood price inflation than for food price inflation. But, its effects fade out quickly. (Earlier I wrote that M2 does not have traction on inflation). Monetary tools have not been used to manage inflation.

- The appreciating nominal effective exchange rate has a negative and lagged impact on inflation only between 2007 and 2011 dataset. [It might be due to rising imports in recent years.]

- Responsiveness to international oil prices and exchange rate has increased lately. That is why international oil prices show a stronger effect in the 2007-2011 dataset.

- Food price increases have contributed about three-fourths of overall CPI inflation, while nonfood prices contributed the remaining one-fourth. Food price inflation has been more volatile than nonfood price inflation.

Food price inflation

- The responsiveness of food price inflation is significant and quick to spillovers from India’s food inflation and oil price movements. Furthermore, the impact of oil prices is more persistent than India’s food inflation. It intensified in recent years. It might be because the price of petroleum products gets reflected faster in the price of chemicals and fertilizers used in agriculture production, transportation cost of agriculture products and use of energy in irrigation, says the report.

- Nominal effective exchange rate has a negative effect on food inflation with a lag of about three months in 2007-2011 dataset only.

- Monetary responsiveness to food price inflation is significant in 2007-2011 dataset, but the effect fades out quickly.

Nonfood price inflation

- Monetary responsiveness to nonfood price inflation is strong in both full and subset dataset series (with largest impact on the full dataset). But, the effects are short.

- Nonfood price inflation responds to Indian food and nonfood inflation as well as international oil prices (strongly since 2007).

- Nominal effective exchange rate has a negative effect on nonfood price inflation between 2007-2011 dataset only.

In a study of similar nature in 2007, Edimon Ginting shows that inflation in India and inflation in Nepal tend to converge in the long run, but the pass through of inflation from India to Nepal take about seven months. Now, this seems to have been violated especially after 2007 due to the strong impact of petroleum prices.

Here is how there is disconnect between Indian and Nepalese inflation rates. I wrote this one last year and is still valid.

- In the long term, inflation is primarily affected by money supply. In the short term, it is affected by demand and supply pressures, which in turn are dictated by relative elasticity of wages, prices and interest rates. The inflationary pressure in the short term could drag into medium term and long term, leading to high inflation for an extended period of time. It happens if prices and wages are too sticky at high level, i.e. once prices and wages rise either due to demand or supply pressure, or both, even if pressures subside, they continue to remain at high levels. This is happening in the economy since 2007.

- One of the reasons why prices remain sticky at high levels (i.e. domestic prices do not come down even when market conditions normalize) is because of various non-economic factors constraining the functioning of markets.

- The global economy was struck by a rapid rise in commodity and food prices in 2007, severely affecting net food importing developing countries like Nepal. Several countries, including India, banned export of key agricultural items imported by Nepal. The shortage of agricultural goods led to rapid rise in domestic prices. Then came a sudden rise in global fuel prices in 2008, leading to a drastic increase in petroleum prices in the domestic market. This directly reduced real disposable income because a substantial portion of the population banks on petroleum products for daily need. It also shot up cost of production of domestic producers, resulting in rising prices of consumer goods and services. The combined effect of the rise in food, commodity, and fuel prices led to spiraling prices starting 2007.

- Unfortunately, when fuel, commodity and food prices cooled down in the international market, the hangover persisted in our economy. Prices stubbornly remained sticky at high levels. Exogenous factors such as supply bottlenecks due to extended periods of bandas and strikes led to shortage of essential items. Additionally, hoarding, black marketeering, deliberate withholding of supplies and inventory, and agricultural trade hurdles imposed by our neighbors contributed to keeping prices higher even after the normalization of market forces.

- These series of events contributed to higher inflationary expectations, leading to a situation where workers, employers, producers, wholesalers and retailers started inflating wages and prices on expectation that inflation will go up. The final outcome was a permanently higher inflation. It might go even higher if the supply side constraints and inflationary expectations are not timely and adequately addressed.

Here is another piece I wrote in 2009 and the arguments still hold true.