This is adapted from the issue focus section of Macroeconomic Update, August 2015, Vol.3, No.2 (executive summary here, and FY2016 growth and inflation outlook here). It includes FY2015 update on real, fiscal, monetary and external sector, and growth and inflation outlook for FY2016. It provides a comprehensive macroeconomic assessment, including fiscal sustainability, after the April 25 earthquake.

I. Introduction

A catastrophic 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck Barpak of Gorkha district on 25 April at 11:56 AM. In between numerous aftershocks of below 5 magnitude, two powerful 6.7 magnitude (26 April) and 7.3 magnitude (12 May) aftershocks shook a large part of the country, particularly central and western administrative regions. It caused further damage to the already weakened houses and physical infrastructure, and also triggered numerous landslides in the rural areas. The calamity has added a new challenge to Nepal’s short-to-medium term economic growth and development prospects.

The completion of post disaster needs assessment (PDNA), establishment of a National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) the reconstruction-focused budget and monetary policy for FY2016, and the gradual improvement in political environment have put in place the key prerequisites for the execution of reconstruction programs. Now, effectively operationalizing the NRA along with immediate planning and strategizing of reconstruction projects is critical for ensuring a fast and inclusive recovery. The NRA’s and sector ministries’ ability to swiftly prepare and implement the viable reconstruction projects will be a key determinant for speedy restoration of livelihoods and economic recovery.

The estimated 700,000-982,000 additional people pushed below the poverty line by the earthquake-induced income shock need to be pulled back above the line by providing them with jobs, skills and social protection as appropriate. The post-reconstruction programs need to be well coordinated, ensure ‘building back better’, and be an integral part of the larger goal of meaningful structural transformation of the economy.

II. Damages to lives and property

Over 8,800 were confirmed dead and 22,309 injured. Furthermore, 602,257 and 285,099 private houses were fully and partially damaged, respectively, forcing thousands of people to seek temporary shelter under tents and tarpaulin sheets. Furthermore, 2,673 and 3,757 public buildings were fully and partially damaged, respectively. To prioritize rescue and relief operations, the government declared 14 districts as severely affected (mostly in the central and western regions) although the earthquake has affected 31 of Nepal’s 75 districts.

III. Post disaster needs assessment

According to PDNA estimates, the cumulative damage and loss amount to 33.3% of GDP ($7.1 billion) and the cumulative need for recovery is estimated at $6.7 billion (31.5% of GDP). PDNA was spearheaded by the National Planning Commission with the support of various government agencies, development partners and civil society. It included 21 sectoral and thematic assessments.

| Damages, losses and needs ($ billion) |

| Sector | Included sectors | Damage | Loss | Total needs |

| Social | Cultural Heritage, Education, Health and Population, Housing and Human Settlements | 3.5 | 0.5 | 4.0 |

| Productive | Agriculture, Financial Sector, Industry and Commerce, Irrigation, Tourism | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Infrastructure | Communications, Community Infrastructure, Electricity, Transport, Water and Sanitation | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Cross-Cutting | Gender, Social Protection, Nutrition, Employment & Livelihoods, Disaster Risk Reduction, Environment and Forestry, Governance | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Total | | 5.1 | 2.1 | 6.7 |

Source: National Planning Commission

Of the total estimated recovery needs, about 50% is for rebuilding private housing and settlement. Productive and infrastructure clusters need 17.3% and 11.1%, respectively. These amount to about 5.5% and 3.5% of GDP, respectively. The recovery needs requirement for agriculture, education, electricity, and transport is estimated at $156 million, $397 million, $186 million, and $282 million, respectively. Furthermore, recovery of the tourism sector and restoration of cultural heritage are estimated to require $387 million and $206 million, respectively.

IV. Impact on economy

On 8 June 2015, the Central Bureau of Statistics estimated the macroeconomic impact of the earthquake. GDP growth (basic prices) is estimated to decline by over 1.5 percentage points to 3.0% in FY2015. Pre-earthquake growth estimate for FY2015 was 4.6%. Although the earthquake struck Nepal only in the tenth month of FY2015, the impact on GDP growth is sizable, especially on the services sector.

GDP growth (at basic prices), %

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics

Agricultural sector is expected to grow by 1.9%, industry by 2.7%, and services by 3.9%, down from earlier no-earthquake scenario forecasts of 3%, 3.5%, and 5.8%, respectively. The sharp drop in agricultural output is primarily due to the negative impact of delayed and weak monsoon in the first half of FY2015, and later the loss of livestock due to the earthquake.

The slowdown in the industry sector is due to the drastic drop in quarrying (stones, aggregates, sand and soil extraction slowing down in the affected districts, and the government’s policy to temporarily halt construction activities till mid-July 2015); manufacturing (physical damage, labor shortage, and weak demand); and construction (policy to temporarily halt construction activities, and low production of construction materials, among others).

The disruptions caused by the earthquake have been the most severe in the services sector. Overall, services growth is estimated to decline by about 2.1 percentage points to 3.9% in FY 2015. It grew by 6.4% in FY2014. Wholesale and retail trade; tourism activities (affects air transport, and hotel and restaurant businesses); real estate, renting and business activities; and education sub-sectors are the most affected.

Impact of earthquake on sectoral growth (%)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics

Wholesale and retail trade grew by 9% in FY2014, but dropped to 3.4% after the earthquake (against the pre-earthquake forecast of 5.6%) in FY2015. This is primarily due to the slowdown in agricultural production and import of goods immediately after the earthquake. Hotels and restaurants suffered due to slowdown in tourist arrivals, physical damage to hotels and restaurants, and decline in domestic tourism. Furthermore, real estate activities were in line with the substantially lower land-related transactions (including buying and selling, renting, and operation of self-owned or leased real estate; and renting of machinery, equipment and personal and household goods). There was also a substantial slowdown in property renting business due to the physical damage to buildings.

Overall, agricultural, industry, and services sectors will contribute 0.6, 0.4, and 2.1 percentage points to GDP growth of 3% (at basic prices) in FY2015, respectively. Nepal’s GDP is estimated at $21.6 billion in FY2015 ($371 million less than what would have been in a no-earthquake scenario). The loss is equivalent to 1.5% of GDP, and about 62% of the total gross value added[1] (GVA) loss is accounted for by the services sector.

Value added output loss by sub-sector in FY2015 ($ million)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics

Per capita income is estimated to decrease by $23 compared to the no-earthquake scenario (in which case per capita income would have been $785). Accordingly, real per capita income increased by just 0.6% against 3.6% in a no-earthquake scenario.

Nominal per capita GDP (US$)

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics

Inflation was moderating till mid-April 2015, but it started edging up as a result of the supply-side disruptions caused by the earthquake. Prices of both food and non-food items increased in the last three months of FY2015, resulting in an average inflation of 7.2%.

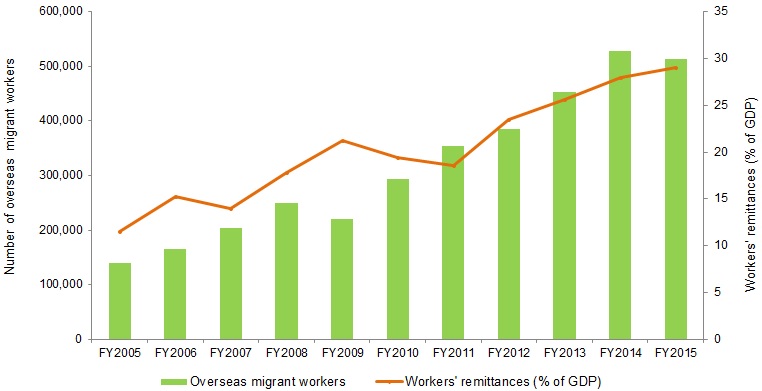

External sector stability remained robust as net transfers increased sharply than the rise in trade deficit, resulting in a current account surplus of 5.1% of GDP and a record foreign exchange reserves ($8.3 billion, which is sufficient to cover 11.2 months of import of goods and nonfactor services). However, this may not be sustained for long as import of construction items is expected to increase drastically in the next few years for the post-earthquake reconstruction programs. Consequently, growth of net transfers may stabilize as migrant workers deplete their present and anticipated savings by remitting early to help households meet immediate needs. Furthermore, remittance inflows may also slowdown if there is less demand for workers in the Gulf countries and Malaysia following the cost-free migration policy[2] implemented by the on July 2015. Hence, the current account balance may slip into the negative territory over the medium term and foreign exchange reserves may deplete to an equivalent of around 7 months of imports, which is also the recommended level of reserve adequacy to ensure external sector stability.[3]

V. Impact on poverty and MDGs

The severely earthquake-affected 14 districts account for about 13.6% of the total number of people living below the poverty line in Nepal. Among them, Dolakha, Makwanpur, Ramechap, Rasuwa, Sindhuli, and Sindhupalchowk have higher poverty rate than the national average of 25.2% in 2011. Similarly, nine have human development index (HDI) score lower than the national average.

Preliminary estimates show that the income shock as a result of the earthquake will likely push an additional 700,000-982,000 people below the poverty line. This translates into an additional 2.5%-3.5% of the estimated population in 2015 pushed into poverty compared to the no-earthquake baseline scenario of about 21%. About 50%-70% will come from rural Central hills and mountains, where the vulnerability prior to the earthquake was already high. The income shock is largely felt through the loss of livelihoods (including death and injuries to primary wage earners) and the loss of housing, productive assets (seeds, livestock, and farm equipment), and durable assets (assorted household items).

Beyond this monetary-based poverty estimates, a larger impact can be expected when factoring in multidimensional poverty, which includes additional factors such as water and sanitation services, disruption of schools and health services, and the possibility of an uptick in food insecurity. The poor and vulnerable are particularly dependent on local infrastructure (roads, bridges, health posts, and schools) for access to labor and commodity markets, and for accumulation of human capital (especially those of children). Reviving local economic activities and resumption of basic public services along with an accelerated implementation of reconstruction projects will be critical to make up for the setback on poverty reduction caused by the earthquake.

Furthermore, the progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), on which Nepal was mostly on track prior to the earthquake, is likely to be adversely affected, given the widespread damages to houses, classrooms, and health posts. It will also likely affect the country’s overarching goal to graduate from the Least Developed Country (LDC) category by 2022.

VI. International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction

On 25 June 2015, the government organized an international conference on Nepal’s reconstruction. High level representatives from over 50 countries and multilateral agencies participated in the conference.

ADB, represented by its President, Takehiko Nakao, pledged $600 million—including $200 million emergency assistance approved by its Board of Directors on 24 June—to support rebuilding of schools, roads, and public buildings. The government estimated the total pledge of assistance at $4.0 billion (equally spilt in grants and concessional loans). Of the total pledge, about 67% is new commitment ($2.7 billion). Cumulatively, India and the Peoples’ Republic of China committed $1.4 billion and $767 million, respectively. World Bank, Japan, the US and the EU pledged $500 million, $260 million, $130 million, and $117 million, respectively.

According to the PDNA, total public sector losses and damages amount to $1.7 billion, which excludes housing. The National Planning Commission estimated that about 57% of the recovery needs ($3.8 billion), including housing, will have to be shouldered by the government. In this respect, the total pledged amount was higher than the public sector recovery needs till the medium-term. However, a much higher amount of investment may be needed in the long-term to build better and earthquake-resilient public infrastructure throughout the country.

Total aid pledged for reconstruction ($ million)

Source: Ministry of Finance; ADB staff estimates

VII. FY2016 Budget and Monetary Policy

The FY2016 budget is primarily focused on rehabilitation and reconstruction of physical and social infrastructure, housing and livelihoods after the catastrophic earthquake.

Completing of reconstruction work within the next five years is the most prominent agenda. It commits to fully operationalize the NRA soon, with a special implementation authority, effective leadership, and adequate financial resources. A total of NRs91 billion ($910 million or 3.8% of GDP) has been earmarked for reconstruction work, including $740 million (3.1% of GDP) for the National Reconstruction Fund, which will initially prioritize reconstruction of housing, public buildings, archeological structures, physical infrastructure, and enhancement of productive capacity. About $170 million is earmarked for sector ministries and agencies to carry out reconstruction works till the NRA is operational, i.e. an interim arrangement.

Planned reconstruction budget for FY2016 and composition of National Reconstruction Fund (NRs billion)

Source: FY2016 Budget Speech

The budget also includes NRs200,000 (about $2000) for each household that has lost its house due to the earthquake. To address the shortage of labor for reconstruction, skill training is planned for 50,000 people in the areas of masonry, plumbing, and electrical works.

Meanwhile, to assist government, Banks and Financial Institutions (BFI), and the public in their efforts toward accelerated post-earthquake recovery, Nepal Rastra Bank (the central bank) introduced a number of measures in the monetary policy for FY2016, including:

- Zero percent refinancing facility for BFIs willing to provide loans at 2% interest to those households affected by the earthquake, provided that such households meet the requirements set by the government. Accordingly, households within and outside Kathmandu Valley can access the subsidized loans of up to NRs2.5 million and NRs1.5 million, respectively.

- As announced in the FY2016 budget speech, the NRB will help assist in the establishment of an Economic Rehabilitation Fund, which will provide refinancing facility and interest subsidy to the business community affected by the earthquake.

| Breakdown of reconstruction budget for FY2016 |

| NRs billion | GON | Grant | Loan | Total | Share of aid |

| National Reconstruction Fund | 16 | 36 | 22 | 74 | 78 |

| Recurrent expenditure | 8 | 15 | 12 | 35 | 77 |

| Program expenses | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Capital grants to institutions & individuals | 6 | 15 | 12 | 33 | 82 |

| Capital expenditure | 8 | 21 | 10 | 39 | 79 |

| Building construction | 2 | 10 | 5 | 17 | 88 |

| Civil works | 6 | 11 | 5 | 22 | 73 |

| Natural disaster relief & reconstruction | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| Recurrent expenditure | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Capital expenditure | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| Civil works | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Capital contingencies | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Capital formation | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

Source: FY2016 Red Book; Budget Speech

| | | | | | VIII. Effective reconstruction and recovery

Recovery has to be faster, better and smarter given that the country lies on an active geological fault lines. Drawing from ADB’s experience in post-disaster recovery in Asia and the Pacific region, ADB President Nakao highlighted, during the reconstruction conference, five principles for effective reconstruction that Nepal could follow:

-

Public as well as private buildings should be rebuilt to earthquake-resilient standards, fully applying the principle of “Build-Back-Better”.

-

Inclusiveness should be at the core of reconstruction effort. Special attention should be paid to the needs of the poor, rural residents, and other vulnerable social groups, who have suffered more from the earthquakes.

-

A robust institutional setup for reconstruction is pivotal to successfully execute reconstruction projects within the given timeframe. A strong leadership and competent human resources are vital for the success of the NRA.

-

Continuous enhancement of the institutional capacity of executing and implementing agencies along with the adoption of sound governance and fiduciary risk management systems for the reconstruction process are also important.

-

Effective donor coordination and strong government ownership of the entire process are also equally important for the success of the reconstruction projects.

He also emphasized that reconstruction should go hand in hand with development programs already planned, without affecting the latter.

IX. Accelerated recovery and structural transformation

The reconstruction authority’s and sector ministries’ ability to swiftly prepare and implement viable projects will underpin the scope and pace of reconstruction, and hence the recovery phase. A coherent reconstruction strategy has to be ideally aligned with the long-term economic development vision, which aims to increase per capita income to the level of a middle-income country before 2030. This is especially important because the PDNA covered earthquake-resilient reconstruction only in the affected areas, whereas this has to be implemented throughout the country. Adhering to the principle of Build-Back-Better, t rebuilding damaged houses beyond the set size, retrofitting standing buildings in Kathmandu Valley and affected districts, and nationwide resilience (such as ensuring housing and school safety across the country) need to be kept in mind while planning and initiating rehabilitation and reconstruction projects.

Overall, rehabilitation and reconstruction should primarily aim at increasing productivity-enhancing public capital investment. This is a key to ensuring structural transformation whereby high value-added and high-productivity sectors are more dominant than low value-added and low-productivity sectors in the medium term. Promoting agribusiness, industrial capacity, innovation and high-productivity services need to be at the center of such a reconstruction and structural transformation strategy. In addition to higher investment, this will require reforms on institutional, legal, regulatory, and capacity enhancement fronts.

Structural transformation

Source: Authors’ estimate

Private investment has been suppressed primarily due to the liberal product market (including imports), but an unreformed factor market (land, labor, and capital) after 1992 (the time when the first set of liberalization reforms were rolled out). This has led to stunted growth of the manufacturing sector and its declining share of GDP as imported-based activities expanded. Given this background, a higher quantum and quality[4] of capital spending is vital to boost aggregate demand, expand the growth potential of the economy, and increase per capita income. Higher productivity-enhancing public capital investment would also increase returns on private investment, resulting in higher private investment due to the ‘crowding-in’ effect. Such public investment over the medium term in physical and social infrastructure enhances productivity growth, encourages technological innovation, accelerates recovery and establishes a faster, inclusive, and sustainable growth pattern. However, in the long term, structural changes, especially in factor markets (land, labor, and capital), are required to sustain the growth pattern established through stabilization measures over the medium term.

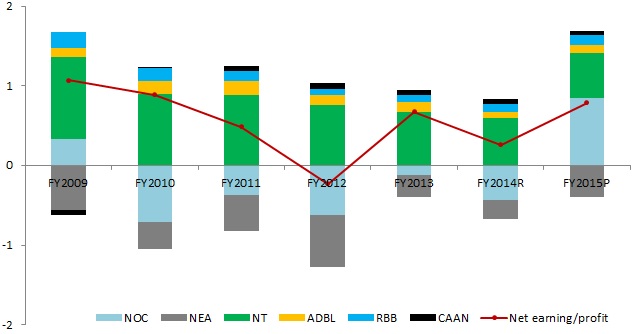

X. Concerns over effective budget execution

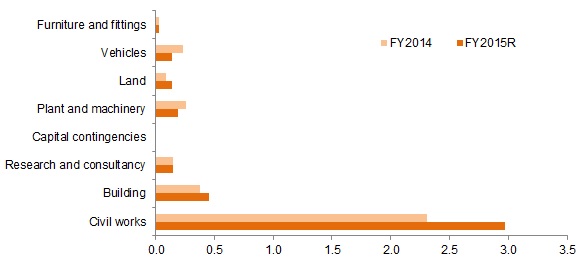

One of the biggest unknowns following the decision to establish the NRA is its ability to fully execute the planned reconstruction budget in well-planned productivity-enhancing projects. This concern arises from the persistent budget execution shortfalls even under normal circumstances, which has further weakened in the last decade. As such, actual capital spending averaged about 72% in the last decade and about 60% is bunched in the last quarter. Furthermore, the actual capital spending (about 3% to 4 % of GDP) is far less than the required spending (of 8-10% of GDP) to close the infrastructure gap..

Planned and actual capital spending (% of GDP)

Note: Changed reporting system to Government Finance Statistics (GFS) 2001 in FY2012. In FY2011, actual reporting was done based on GFS 2001, but budget allocation was done based on earlier GFS.

Source: Ministry of Finance; NRM staff estimates

Capital spending is marred mainly by:

-

Bureaucratic hassles: project approval delays, and weak intra and inter-ministry coordination,

-

Structural weaknesses: limited appraisal, planning, and implementation capacity of line ministries (including the lack of medium-term expenditure framework), lack of strong pipeline of projects ready for implementation, cumbersome laws and regulations (procurement and procedural clearances), and allocative inefficiency,

-

Low project readiness: lack of feasibility studies and detail designs in advance, lack of well-planned procurement plans, and delays in land acquisition,

-

Weak project management: high staff turnover, lack of staff capacity, lengthy procurement process, weak contractor capacity, and weak contract management

-

High fiduciary risks in project implementation, particularly in rural areas when programs are implemented through local government having limited human resources and capacity,

-

Political instability and interference at operational level

The budget for FY2016 partially addresses this concern by giving the line ministries administering large projects the authority to spend the planned budget without getting prior approval from the NPC and the MOF. Similarly, multi-year contracts are allowed for some projects and the government has committed to restrict transfer key project staff subject to satisfactory progress in implementation. Deployment of managers, accountants, and technical staff is envisaged in village development committees starting with earthquake affected areas. However, other issues outlined above impeding regular capital spending remain unchanged and it is likely that $170 million allocated to various line ministries for reconstruction work may remain underspent at the end of FY2015.

With regard to spending by the NRA, the ordinance, which needs to be transformed into an Act without delay, governing its establishment gives it sweeping powers to do away with most of the hassles impeding accelerated capital spending. The authority is chaired by the Prime Minister and its CEO will independently handle the operations. The CEO, whose performance will be critical to accelerated reconstruction within the given timeframe, was still not appointed two months after the ordinance for its establishment was introduced. This already delayed the pace of implementation, especially concerning hiring of human resources, preparing a quick pipeline of projects, an associated action plan for investment, and its overall synchronization with the long-term development vision being envisaged by the NPC. The faster the NRA comes into operation, the faster will be the capital spending and ultimately completion of the reconstruction programs.

The NRA will have a critical role in managing the following crucial issues for accelerated reconstruction and recovery:

-

Hiring competent human resources that can bring in new and smarter ideas and foster innovation (including reassigning competent civil servants from across government departments)

-

Preparing a credible time-bound action plan for investment in reconstruction projects, including a sizable pipeline of potential projects

-

Managing political interference in normal operations and preparation of reconstruction projects and ensuring an inclusive development process

-

Ensuring line ministries’ full ownership of projects designed, approved and procured by the NRA

-

Coordinating with development partners to ensure that the committed funds for reconstruction are realized within the given timeframe

-

Engaging meaningfully youth, local communities, think tanks, specialized institutes, and civil society in reconstruction planning, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation

-

Ensuring ‘crowding-in’ of private investment for reconstruction on public-private partnership (PPP) basis

-

Outsourcing of managerial as well as non-managerial work (time and output-bound contractual arrangement for design, supervision, and management of reconstruction projects).

XI. Conclusion

The earthquake caused tremendous loss of lives and properties. It lowered economic growth rate, pushed about a million people below the poverty line, slowed progress on achieving some of the MDGs, and sapped investors and consumer confidence. The cumulative pledges during the international reconstruction conference exceeded the expected public sector needs for reconstruction. Now, the NRA and line ministries’ ability to swiftly prepare and implement viable projects will underpin the scope and pace of reconstruction and ultimately a better, faster and smarter recovery. The authority needs to be operationalized without delay and it has to chart out a coherent five-year reconstruction strategy by aligning it with the long-term economic development vision.

Accelerated reconstruction would require hiring of competent human resources, preparing a time-bound investment action plan, a strong pipeline of viable projects, outsourcing of design, monitoring and evaluation, political buy-in of proposed actions, and engaging youth, specialized institutions, and civil society at various stages of the project cycle. This would then ‘crowd in’ private investment as well, leading to a higher, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth. Overall, rehabilitation and reconstruction should primarily aim at increasing productivity-enhancing public capital investment, which is a key to ensuring structural transformation whereby high value-added and high-productivity sectors are more dominant than low value-added and low-productivity sectors in the medium term.

[1] Gross output is the total value of all goods and services produced during the accountancy period (at basic prices). Intermediate consumption is the total value of goods and services consumed as inputs by production processes (at purchasers’ prices). Gross value added is the difference between gross output and intermediate consumption. Finally, GDP is equal to gross value added plus taxes minus subsidies.

[2] The Ministry of Labor and Employment directed overseas recruitment agencies to facilitate migration without financially burdening the migrant workers. This essentially means cost-free migration for workers seeking employment in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman and Malaysia.

[3] IMF. 2015. Nepal: Request for Disbursement Under the Rapid Credit Facility. IMF Country Report No.15/224. Washington, DC. See: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15224.pdf

[4] Low quality of capital spending escalates future recurrent costs associated with the project (such as operation and maintenance costs, staff required to monitor the project, etc)