Professor Tyler Cowen argues that empty rice bowls can be filled if there is more freer trade in foodstuffs (only about 5-7% of total rice production is traded across borders). He thinks that in the long-run restrictions on food exports is going be counterproductive.

..Restrictions on the rice trade run the risk of making shortages and high prices permanent. Export restrictions treat rice trade and production as a zero- or negative-sum game where one country’s gain comes at the expense of another. That’s hardly the best way to move forward in a rapidly growing world economy.

This lack of support for trade reflects a broader and disturbing trend. An increasing percentage of the world’s production, including that for agriculture, comes from poor countries. Over all, that’s good for rich countries, which can focus on creating other goods and services, and for the poor countries, which are producing more wealth. But it can slow the speed of adjustment to changing global conditions.

...Many poor countries, including some in Africa, could be growing much more rice than they do now. The major culprits include corruption in the rice supply chain, poorly conceived irrigation systems, terrible or even nonexistent roads, insecure property rights, ill-considered land reforms, and price controls on rice.

...The sadder truth is that when it comes to food production — arguably the most important of all human activities — Mr. Friedman’s free-trade ideas still haven’t seen the light of day.

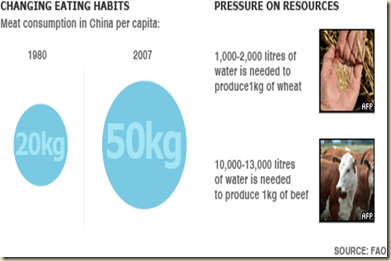

Okay, honestly this is yet another attempt to fully justify the virtues of free markets and free trade. Cowen explains basic economics about trade and relates it with the stuff going on in the Philippines and other countries. However, he stretches this analysis too far by bringing Friedman into his explanation. We know that free trade and all the efficiency and productivity arguments related to it are possible only when there are no distortions or inefficiencies in other complementary factors. For instance, how would Nepal and Burkina Faso benefit from freer trade in rice if the transportation cost is at least 30% over the price of foodstuff. Moreover, if there is freer trade (which is unlikely without revision of the Doha Round given the economic and political constraints...though I root for more open markets but with some caution), then major rice producers like India, Vietnam, and Egypt, among others would be the only producers in the long run because it would 'creatively destruct' meager rice production in, say, Nepal and Burkina Faso (I am not sure whether there will be creative creation of new rice producers because those who can have been producing since decades). The relatively cheaper (if any) rice from major producers (remember economies of scale, mass production, and cheaper price leading to existence of few big companies in the market...and who knows they might jack up prices again) would take over markets all over the world. This is fine but what if some emergency happens or a major policy shift occurs, which would disrupt the supply chain. Well, people from net importers would again have empty bowls!

Anyway, the dictates of Friedman would not work precisely because there is "corruption in the rice supply chain, poorly conceived irrigation systems, terrible or even nonexistent roads, insecure property rights, ill-considered land reforms, and price controls on rice." Tyler admits the existence of these inconsistencies (which are going to stay with us because of greedy and self-interested nature of human beings) but still repents that "Mr. Friedman’s free-trade ideas still haven’t seen the light of day.". I sense some contradictions! Also, the incentives thing Cowen talks about is pretty hard to come by. How would farmers up in the mountains in Bhutan, Nepal, India or farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa get incentives to grow more rice, even in the face of higher prices in the international market, if they do not have control over land, lack credit to buy seeds and fertilizers, bear higher transportation cost, and, most importantly, are very unsure about climatic factors. There are so much lags in information dissemination, procurement of seeds, harvesting, and accessing the markets.

Farming in the emerging markets (and developing countries) is riddled with market failures and does not react to price signals as other businesses do. This sector is sticker than any other sector (a 10% increase in prices leads to a 1% increase in output), and there are numerous bottlenecks, such as lack of access to finance- the main reason why Kenyan and Ethiopian farmers planted less this year. Even if there is substantial move towards free trade (hopefully, under a revised Doha Round), bottlenecks and market failures would decrease the pace of transition to a new equilibrium. The adjustment process Cowen talks would be very slow and might in fact make some countries much more worse off.

Meanwhile, Rodrik disagrees with Cowen's assertion that freer trade would boost global supplies and lower prices. He uses similar basic economics arguments to assert that the net effect would depend on whether a country is net importer or net exporter of food in the international market. If a country is a net importer, then it would see lower prices. However, if a country is net exporter, then its domestic market would see higher prices relative to other products. Relative to the international market prices, domestic prices would be lower but when there is higher demand, it also pushes domestic prices up, which might still be cheaper to customers from other countries. See more here

Trade works by relieving the relative scarcity of goods. The key here is the term "relative." Food importing countries are food scarce countries, and as they open up to trade, the relative price of food falls. But if you are Thailand or Argentina, where other goods are scarce relative to food, freer trade means higher relative prices of food, not lower. And all the induced efficiency benefits and short- vs. long-run effects that Cowen talks about have no bearing on this conclusion: in the end some countries have to be net importers, and others net exporters.

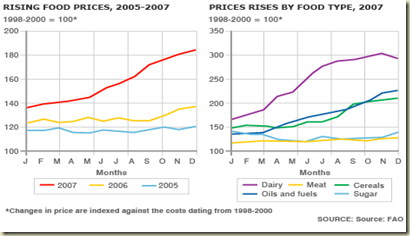

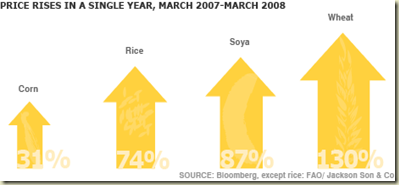

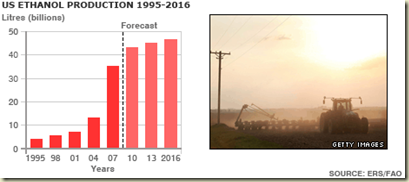

Here is Esther Duflo's take on rising food prices. Here is food crisis in figures and charts.

Spence presented the main findings of his paper. He argued that the advanced countries’ model of growth strategies is an incomplete guide but not worthless for the developing countries. He was arguing for the gradualism in growth strategies and polices as seen in China and to a lesser extent in India. Experimental approach is needed for successful navigation of growth strategies and policies, again as done by China. He also argued for the effectiveness of government intervention in key areas to bring coordination in economic activity. Governments should engage in vigorous policy debate with a definite end, i.e. policy wrangling is not enough, there should an end to policy debates and concrete action should follow such debate. Moreover, governments should admit and fix mistakes (especially ex-post determined).

Spence presented the main findings of his paper. He argued that the advanced countries’ model of growth strategies is an incomplete guide but not worthless for the developing countries. He was arguing for the gradualism in growth strategies and polices as seen in China and to a lesser extent in India. Experimental approach is needed for successful navigation of growth strategies and policies, again as done by China. He also argued for the effectiveness of government intervention in key areas to bring coordination in economic activity. Governments should engage in vigorous policy debate with a definite end, i.e. policy wrangling is not enough, there should an end to policy debates and concrete action should follow such debate. Moreover, governments should admit and fix mistakes (especially ex-post determined).

Then Robert Rubin argued that there is nothing wrong with export-led policy in the low income countries. However, the US should cope with the changes in the global economy and focus on distributional and social safety nets in the domestic market. Rubin argued that an effective government is itself an ingredient for growth. Also, he said that a relatively authoritarian government in the early stages of growth has been successful (South Korea, China, Malaysia). The biggest challenge now is: How to promote effective governance with a democratic system?

Then Robert Rubin argued that there is nothing wrong with export-led policy in the low income countries. However, the US should cope with the changes in the global economy and focus on distributional and social safety nets in the domestic market. Rubin argued that an effective government is itself an ingredient for growth. Also, he said that a relatively authoritarian government in the early stages of growth has been successful (South Korea, China, Malaysia). The biggest challenge now is: How to promote effective governance with a democratic system?