Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented INR 34.8 trillion expenditure plan [USD 476.8 billion, USD 1 = INR 73.05 as on Feb 1) for FY2022 (starts 01 April 2021). It is 1.0% increase over the revised expenditure estimate for FY2021. Revenue growth is expected to be 23.4% (15% if we consider revenue plus recovery of loans & divestment receipts).

FY2022 budget focuses on six pillars:

- Health and wellbeing (PM Aatmanirbhar Swastha Bharat Yojana to develop capacities of primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare system, strengthen existing institutions and rollout COVID-19 vaccine, among others)

- Physical and financial capital, and infrastructure (ANB production linked incentive scheme to promote manufacturing activities, mega investment textiles parks, National Infrastructure Pipeline, recapitalization of PSBs, infrastructure financing through Development Financial Institution, national asset monetization pipeline of potential brownfield infrastructure assets; roads, highways and railway infrastructure with focus on corridors; development of world class Fin-tech hub at GIFT-IFSC; divestment of strategic assets such as BPLC, Air India, SCI, CCI, IDBI Bank, etc)

- Inclusive development for aspirational India (focus on agriculture and allied sectors, farmers' welfare and rural India, migrant workers and labor, and financial inclusion incl MSME)

- Reinvigorating human capital (proposed Higher Education Commission of India that will set standard, accredit, regulate and fund higher education; benchmark skill qualifications, assessment, and certification, accompanied by the deployment of certified workforce)

- Innovation and R&D (national research foundation, language translation mission, a space PSU, etc)

- Minimum government and maximum governance (bill to regulate healthcare professions, first digital Census, etc)

The thrust is on Aatmnirbhar Bharat (Self-reliant India) initiative, for which it has rolled out sectoral incentives (such a production linked incentives to spur industrial activities), increase in custom duties on certain items, and sectoral reforms.

Expenditure: Revised total expenditure for FY2021 is estimated to be 113.4% of budgetary estimate for FY2021 as pandemic-related expenditure on providing relief increased. For FY2022, about 84.1% of total expenditure outlay of INR 34.8 trillion consists of revenue expenditure (recurrent expenditure) and the rest 15.9% is capital budget. About 23.2% of the revenue expenditure consists of interest payments, 10% for defense, 9.9% for transfer to states and UTs, and 9.6% for subsidy. Interest payment alone is expected to be 45.3% of total revenue (tax and non-tax revenue).

The expenditure outlay for health sector is down by 9.5% compared to FY2021 revised estimate. It grew by 30% in FY2021 compared to FY2020, reflecting the spike in healthcare expenditure to contain the pandemic. Similarly, allocations for rural development, which includes NREGA, is down 10% compared to 51.9% growth in FY2021.

In addition to INR 34.8 trillion expenditure outlay, the government is also expecting capital investment of INR 5.8 trillion from various public enterprises, resulting in total expenditure outlay of about INR 40.7 trillion. In FY2021, the union government’s expenditure was INR 34.5 trillion and public enterprises spent INR 6.5 trillion in capex, making total expenditure of INR 41 trillion. So, total capital spending of the central government (incl PSUs capex) could be as high as 5.1% of GDP.

Revenue: As per the revised estimates for FY2021, the government expects to mobilize 77% of the tax and non-tax revenue outlined in the FY2021 budget. While tax revenue is expected to be 82.2% of target, non-tax revenue is expected to be just 54.7% of the target. Capital receipts are expected to be 185.6% of budget target, thanks to a massive borrowing after the lockdowns.

In FY2022, the government is expecting to mobilize INR 17.9 trillion revenue, of which 86.4% is tax revenue and the rest 13.6% is non-tax revenue— similar to the revised estimate for FY2021. The government wants to mobilize INR 1.9 trillion in the form of non-debt creating capital receipts (recovery of loans and divestment receipts). A substantial part of it consists of divestment receipts (INR 1.8 trillion). Divestment targets have been missed in the past. For instance, the government could not meet the divestment target in FY2020 (INR 0.5 trillion vs INR 1.05 trillion targeted) and FY2021 (INR 0.32 trillion vs INR 2.1 trillion targeted).

The projected revenue is estimated to be 8.9% of GDP (6.9% tax revenue, 1.1% non-tax revenue and 0.9% non-debt creating capital receipts), which is higher than 8.2% revised revenue estimate in FY2021. Note that non-debt creating receipt is estimated to be about 0.84% of GDP, much higher than 0.24% of GDP last year. This is primarily due to a large divestment target (about 0.79% of GDP, up from 0.16% of GDP in FY2021).

Of the total gross revenue to be mobilized by the center (including transfer to NCCF/NDRF and state’s share), GST accounts for 21.8%, income tax 19.4% and corporation tax 18.9%.

Fiscal deficit: The projected expenditure and revenue including recovery of loans and divestment receipts leaves a budget gap of about INR15.1 trillion for FY2022 (6.8% of GDP). The government wants to finance this fiscal deficit by borrowing and using other resources (including drawdown of cash balance). Specifically, it is planning to borrow almost all of it from the internal market. Specifically, about 64.3% of it will be in the form of market borrowing (dated government securities and T-bills) and the rest from securities against small savings, state provident funds and other receipts including 364-day treasury bills and net impact of switching-off of securities. External borrowing is estimated to be about INR46.2 billion (0.01% of GDP).

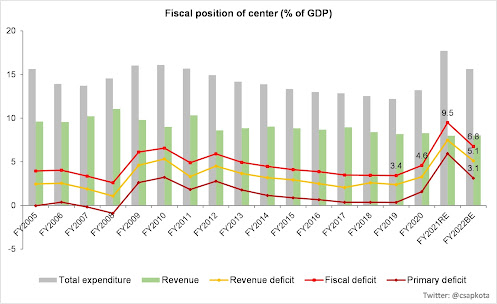

For FY2022, projected revenue deficit is 5.1% of GDP, fiscal deficit 6.8% of GDP, and primary deficit 3.1% of GDP. In FY2021, the estimated revenue deficit is 7.1% of GDP, fiscal deficit 9.5% of GDP and primary deficit 5.9% of GDP.

The reduction in deficit targets primary hinges on the ability of the government to accomplish its divestment target. Divestment of government-held assets is kind of one-off revenue bonanza. Relying on divestment alone to lower fiscal deficit is not going to be sustainable. The government is planning to divest assets in several PSUs (such as Air India, LIC, etc). It is expected to be around 0.79% of GDP, up from 0.16% of GDP in FY2021. The plan for big ticket divestment has been dragging on for a long time.

However, if nominal GDP growth accelerates (more infrastructure investment funding by divesting government-owned assets), then revenue mobilization will also pick up and fiscal deficit could be narrowed. Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act 2018 sets fiscal deficit target at 3% of GDP by FY2021 and central government debt at 40% of GDP by FY2025. The government will amend FRBM Act as it will not be able to bring fiscal deficit to the level stipulated in the existing version of FRBM Act. The finance minister committed, in her budget speech, that the government will bring down fiscal deficit to 4.5% of GDP by FY2026, largely by increasing buoyancy of tax revenue through improved compliance, and increased receipts from assets monetization (including public sector enterprises and land). States are allowed to borrow more next year but will have to lower net fiscal deficit to 3% of GSDP by FY2024.

Starting this budget document, the government will discontinue NSSF Loan to FCI for food subsidy and that it will be provisioned directly in the budget. This applies to FY2021 revised estimate and FY2022 budget estimate. This move improves budget transparency as substantial subsidy related extra budgetary resources were complicating true extent of government borrowing and level of fiscal deficit. In fact, in FY2020 budget, the FM released data on extra budgetary resources, especially borrowings of government agencies that went towards funding GOI schemes and the repayment was the government's burden. In FY2021 budget, the FM extended its scope and coverage to include NSSF loans provided by the government to the FCI. This is now discontinued.

The stimulus measures (Self-reliant India initiatives such as production-linked incentives for 13 key sectors, increase in customs duty to encourage Make in India, increase net borrowing limit for states by 4.0% of GSDP for FY2022 and it could be conditionally increased by 0.5% of GSDP, capex increase, and RBI accommodative measures) and rapid vaccination program are expected to support economic recovery. Some of the rating agencies are okay with the high fiscal deficit along with a realistic (or even conservative) revenue projection.

Concerns over fiscal/debt sustainability and sovereign ratings have been sidelined in favor of higher expenditure to support economic activities. The fiscal situation will be okay as long as GDP growth rate is higher than interest rates on government bonds. Already interest payment by central government is about a quarter of total spending and 45% of total revenue. Higher the borrowing by the government, the higher will be interest payments. It is important that higher borrowing goes into creating productive assets so that the return is more than enough to pay off debt.