In a one pager published this month by the IPC, Kate Bayliss from the Center for Development Policy and Research argues that the South African electricity crisis is a result of the failure of the private sector to respond to an ambitious electricity restructuring and privatization program beginning early 1990s and the lack of public investment in this sector. Bayliss maintains that though power sector is open to the private sector in other countries as well, there has been a decline in investment, implying that just making arguments on investment gap by following the orthodox restructuring economic models of the 80s and 90s would not work.

During the recent power cuts, a very high proportion of generation capacity was out of service. During January 2008, for example, this reached 23 per cent, mostly due to unplanned maintenance.

The Eskom plant is under severe strain due to factors such as poor coal quality, staff shortages and a high load on its capacity. A vicious circle has developed: a high proportion of plant is out of action, so further strain is placed on the existing plant, which becomes even more likely to break down.

Because of this additional strain on the system, frequent outages are inevitable. Similar reform packages have been repeated in much of sub-Saharan Africa. But the ‘unbundling’ of the electricity supply industry to facilitate private sector participation has failed to elicit the critically needed investment.

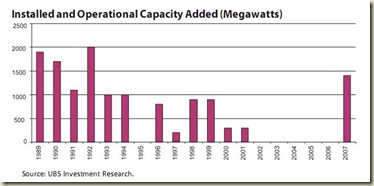

Across all developing countries, private sector investments in the power sector declined from US$ 47 billion in 1997 to US$ 14 billion in 2004. However, international advisors have continued to adhere to the orthodox package of restructuring policies, claiming that obtaining private sector investment is unavoidable because of a widening ‘investment gap’ in the power sector.

Bayliss concludes that in the wake of private sector's failure to tap into the opportunities in the power sector, the state must fill in the tap by investing more in the sector.

The electricity crisis of South Africa demonstrates that the widespread efforts across developing countries to encourage private sector investment in the electricity industry are unlikely to succeed. So the government and state utility must continue to scale up public investment in order to maintain and expand electricity capacity.

Of course, concerns against corruption and malgovernance in the public sector, where ever it might be, would run very high. This does not mean that the state should completely privatize power sector. Both the state and the private sector need to work together to harness untapped resources and opportunities. The state can kick-start the process through initial lump sum investment while keeping in mind that crowding out of private investment is eschewed. Keeping this balance in investment requires good policy work.