With just days to go before Nepal's biggest religious festival of the year, the capital Kathmandu is suffering a severe shortage of goats for ritual sacrifice, the government said Tuesday.

As a result, the government food agency has ordered officials to travel to the countryside and buy up goats to be brought into the capital, where they will be sold for slaughter to mark the main Hindu festival of Dashain.

... the price of the animals had risen by around 25 percent in the capital as the festival approached, and the government was hoping to bring in around 6,000 of them

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Economics at work, Festival edition

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Is Nepal gaining from becoming a member of the WTO?

In my latest op-ed, I look at how Nepal has fared since it joined the WTO in 2004. Quite surprisingly, overall trade has declined and employment situation in the manufacturing sector became worse. May be Nepal should focus more on the nearby markets where trade takes places the most (say, South Asian Free Trade Agreement-SAFTA) rather than eying markets in developed countries.

----------------------------------------------------------------

A recent Ministerial Meeting in New Delhi decided to resume trade negotiations to pass the Doha Round, which came to a grinding halt in July last year over differences concerning special safeguard measures and agricultural subsidies offered by rich nations. The WTO Director General Pascal Lamy hopes that a Doha deal is doable by 2010. The Doha deal is expected to not only help countries expand trade but also help developing countries achieve development goals.

An increase in trade of goods and services in the international market has helped many countries achieve rapid economic growth. In the context of Nepal, we need to inquire what benefits we would have from the Doha Round in particular and the WTO in general. Nepal joined the WTO on April 23, 2004, becoming the first LDC to join the trading bloc through full working party negotiation process. So far, there have not been discernible benefits – in terms of growth, employment, poverty reduction and industrial production – from joining the WTO. In fact, exports have declined, imports increased and the manufacturing sectors, especially the ones that weighted high in the exports basket, have been going downward.

It is time to evaluate the progress made since joining the WTO and the possible impact on growth and employment due to planned reduction in tariffs in the coming years. No study has been done so far to figure out how much would Nepal gain by joining various trading blocs and under what trading scenario (tariff and subsidy rates) would Nepal lose and gain in what kind of sectors? What would be its impact on employment, which should be one of the main barometers for evaluating long-term success of trade?

It is surprising to note that trade (as a percentage of GDP) has declined since 2004, quite contrary to what is expected after joining trading blocs. It was 46.14 percent in 2004 but 45.28 percent in 2007. In the six years before joining WTO, on average, trade was 52 percent of GDP. In post-WTO period, on average, trade was 46 percent of GDP. Imports have been consistently rising since 2004 but exports have been decreasing. In FY 2003/04, exports (as a percentage of GDP) were approximately 16.7 percent whereas it was 12.1 percent in FY 2007/08. However, imports in FY 2003/04 were 29.5 percent of GDP but it was 32.7 percent in FY 2007/08. This means trade deficit is ballooning (increased by 23.3 percent last fiscal year). Had it not been for increasing remittances, balance of payments would have been negative. The investment situation also is not that encouraging. In FY 2007/08, gross investment (percentage of GDP) was 29.7 percent, down from 24.5 in FY 2003/04. Similarly, there has not been much change in foreign direct investment.

This means that even after joining the WTO, the country has failed to reap potential benefits; instead, it is at a disadvantage in terms of export promotion, public investment to prop up key industries and employment generation.

There has been no change in production structure and a shift to new productive activities is not happening. The top five export items – carpets and rugs, garments, jute goods, pulses and raw jute and jute cuttings – have not changed. Almost 80 percent of the exported items are manufactures and 60 percent of total export items go to India. The other top export destinations are the US, the EU, China and Bangladesh. Meanwhile, major import destinations are India (53 percent), China, the EU, Singapore and Malaysia. Of the total imports, 65 percent is manufactures, 15 percent agricultural products and the remaining fuels and mining products.

The rate of increase in volume of trade is not matched by the disappointing progress in economic growth rate and employment generation. The average growth rate in the post-WTO period is 3.5 percent while the average growth rate in trade in the same period is 46 percent. Worse, the employment level has been miserable in the manufacturing sector. Generally, low-skilled manufacturing activities are expected to increase along with a surge in employment in these sectors after joining the WTO. This is true for developing countries where wage rate is low and there is abundance supply of labor. However, in Nepal, the main export industry (garment and carpet) is close to being grounded now, which has already shed almost 90 percent employment and less than 20 firms are in operation.

Two main problems bedevil the exports sector: A lack of price and quality competitiveness. The former is a linked to exogenous factors such as road obstructions, high transportation costs, industrial strikes by politically-motivated trade unions and high cost of procurement of intermediate goods. All of these increase the cost of production. The second one is linked to endogenous factors like unwillingness of the export-based firms to explore innovative means of production and shift production to more productive activities with potential for comparative advantage. It is partly associated to their habit of excessively relying on trade under preferential agreements. A guaranteed low tariff and quota free access to markets abroad led to depression of incentives to innovate by the existing exporters. As per WTO agreement, when the quota system was phased out in 2005, the export-oriented firms went bust because other international competitors started eating up previously guaranteed market share.

The government has not been able to facilitate linkages between productive activities by reducing coordination failures. There are virtually no production and capital linkages between the existing goods that Nepal exports with comparative advantage and those that it could potentially do in the future. The capital and human resources of one industry are not readily available or useful to other industries, leading to a lack of synchronization in innovation of new goods and services.

The process of innovation and synchronization of similar industrial activities have not been made any easier by the government. The talks of establishing special economic zones (SEZ), which comprise of export processing zones, special trading zones, tourism/recreation and simplified banking facilities, have still not materialized due to political bickering and a lack of effective lobby from the industrial sector. The government has been planning for years to establish SEZs in Bhairahawa, Birgunj, Panchkhal and Ramate. Typically, the firms based in SEZs are responsible for producing quality goods and for exporting over 70 percent of their total production. The government has failed to give enough incentives in the form of tax credit, human resource training and technical expertise to the industrial sector.

The stalemate in production structure in the country even after six years of joining WTO is disappointing. No one knows how much will Nepal gain or lose if the Doha Round is completed by 2010. The government and think tanks need to analyze gains and losses under different WTO trading scenarios, especially tariffs reduction and subsidies elimination. Since more than half of the trading activities take place with India, it makes sense to focus on opening up markets for more goods and services between India and Nepal, than with the rest of the world. Also, given the increasing volume of trade among the SAARC members, it might be prudent to seek trading opportunities under much more liberal terms with SAFTA members than hoping to reap far-fetched benefits under the WTO regime.

Source: Republica, September 9, 2009

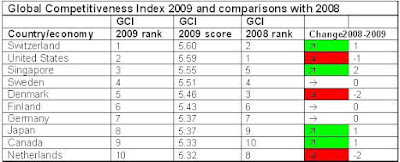

Global Competitiveness Report 2009-2010

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has published its annual global competitiveness report, which ranks countries based on how competitive their economies are (Global Competitiveness Index). This time the US fell to second place, overtaken by Singapore as the most competitive nation.

The GCI is based on 12 “pillars of competitiveness”, providing a comprehensive picture of the competitiveness landscape in countries around the world at all stages of development. The pillars include Institutions, Infrastructure, Macroeconomic Stability, Health and Primary Education, Higher Education and Training, Goods Market Efficiency, Labour Market Efficiency, Financial Market Sophistication, Technological Readiness, Market Size, Business Sophistication,and Innovation.

Here is a list of the top ten competitive nations:

Regarding Nepal’s standing, here are few details:

Overall, it ranks 125 out of 131 nations considered in the report. Specifically, institutions (123), infrastructure (131), macroeconomic stability (86), health and primary education (106), higher education and training (124), goods market efficiency (117), labor market efficiency (122), financial sophistication (99), technological readiness (132), market size (96), business sophistication (126), and innovation (130). Overall, Nepal had four “advantages” and 116 “disadvantages”. Gloomy report for Nepal!

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Doing Business Report 2010--Nepal edition

The IFC has published its annual ease of doing business ranking-- Doing Business Report-- yesterday. This recent report is seventh in a series of annual reports published by the IFC and the World Bank. The report, Doing Business 2010: Reforming through Difficult Times, lists Singapore as a consistent and top reformer this year as well. The other top reformers on the list are New Zealand, Hong Kong, the US, the UK, Denmark, Ireland, Canada, Australia, Norway, and Georgia. Here is the full ranking. Here is an overview.

The report notes that despite global economic crisis, over 70 percent of the 183 economies covered by the report made progress. Reformers around the world focused on making it easier to start and operate businesses, strengthening property rights, and improving commercial dispute resolution and bankruptcy procedures.Two-thirds of the reforms recorded in the report were in low- and lower-middle-income economies. For the first time a Sub-Saharan African economy, Rwanda, is the world’s top reformer of business regulation, making it easier to start businesses, register property, protect investors, trade across borders, and access credit. The top ten reformers for this year are Rwanda, Kyrgyz Republic, Macedonia, FYR, Belarus, UAE, Moldova, Colombia, Tajikistan, Egypt, and Liberia. Rwanda has made fascinating progress in almost all the indicators.

The major indicators used are: starting a business, dealing with construction permits, employing workers, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, and closing business. Note that these indicators do not assess market regulation or the strength of the financial infrastructure; macroeconomic conditions, infrastructure, workforce skills and security.

However, the regulatory environment for business influences how well firms cope with the crisis and are able to seize opportunity when recovery begins. Where business regulation is transparent and efficient, it is easier for firms to reorient themselves and for new firms to start up. Efficient court and bankruptcy procedures help ensure that assets can be reallocated quickly. And strong property rights and investor protections can help establish the basis for trust when investors start investing again.

So, how come the countries that are always in the top ten list consistently and persistently sticking around the top. It is because:

They follow a longer-term agenda aimed at increasing the competitiveness of their firms and economy. Such reformers continually push forward and stay proactive. They do not hesitate to respond to new economic realities. Consistent reformers are inclusive. They involve all relevant public agencies and private sector representatives and institutionalize reforms at the highest level. Successful reformers stay focused, thanks to a long-term vision supported by specific goals.

In South Asia, Pakistan was the top reformer, followed by Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, India, and Afghanistan. It is surprising that India is in the second last position in South Asia.

How is Nepal doing this year?

Nepal’s rank is unchanged at 123 position in terms of ease of doing business. Specifically, starting a business was harder in Nepal (rank 87 in 2010 but 75 in 2009); dealing with construction permits was slightly harder (rank 131 in 2010 and 130 in 2009); employing workers also became difficult (rank 148 in 2010 but 147 in 2009); registering property became easier (rank 26 in 2010 and 29 in 2009); getting credit became difficult (rank 113 in 2010 but 109 in 2009); protecting investors became harder (rank 73 in 2010 but 70 in 2009); paying taxes also became harder (rank 124 in 2010 but 111 in 2009); trading across borders became cumbersome (rank 161 in 2010 but 159 in 2009); no change in enforcing contracts (ranking maintained at 122); and no change in closing business (ranking maintained at 105).

Overall, there was improvement in just one indicator-- registering property. Nepal’s Finance Act 2008 reduced the fee for transferring a property from 6 percent to 4.5 percent of the property’s value. Nepal did not make doing business any easier in the economy this year as well and it languished at the bottom. It is kind of expected because of transportation obstructions, forced closure of industries, labor union strikers, depleting industrial security, no improvement in infrastructure, severe power shortage, and labor market rigidities.

In order to start a business in Nepal, it still takes 7 procedures, 31 days and cost equivalent to 53.6 percent of income per capita. This cumbersome process and high cost exist despite no minimum capital requirement for starting a business. Compare this with doing business in South Asia: it takes 7.3 procedures, 28.1 days, cost equivalent to 27 percent of income per capita, and minimum capital requirement equivalent to 26.9 percent of income per capita.

In dealing with construction permits (the procedures, time, and costs to build a warehouse, including obtaining necessary licenses and permits, completing required notifications and inspections, and obtaining utility connections), it takes 15 procedures, 424 days, and cost equivalent to 221.3 percent of income per capita. Compare this with South Asia,it takes 18.4 procedures, 241 days, and cost equivalent to 2310.6 percent of income per capita. Compare this with OECD average: it takes 15.1 procedures, 157 days, and cost equivalent to 56.1 percent of income per capita.

In employing workers, the difficulty of hiring index is 67, rigidity of hours index is zero, difficulty of redundancy index is 70, rigidity of employment index is 46, and redundancy costs is equal to 90 weeks of salary. Compare this with South Asia: the difficulty of hiring index is 27.8, rigidity of hours index is 10, difficulty of redundancy index is 41.3, rigidity of employment index is 26.3, and redundancy costs is equal to 75.8 weeks of salary. And, to OEDC average: the difficulty of hiring index is 26.5, rigidity of hours index is 30.1, difficulty of redundancy index is 22.6, rigidity of employment index is 26.4, and redundancy costs is equal to 26.6 weeks of salary. Note that each index assigns values between 0 and 100, with higher values representing more rigid regulations. The Rigidity of Employment Index is an average of the three indices.

In registering property, it takes 3 procedures, 5 days and cost 4.8 percent of property values. Compare this with South Asia: it takes 6.3 procedures, 105.9 days and cost 5.6 percent of property values. And to OECD average: it takes 4.7 procedures, 25 days and cost 4.6 percent of property values.

In getting credit, strength of legal rights index is 5, depth of credit information index is 2, public registry coverage (% of adults) is zero, and private bureau coverage (% of adults) is 0.3. Compare this with South Asia: strength of legal rights index is 5.3, depth of credit information index is 2.1, public registry coverage (% of adults) is 0.8, and private bureau coverage (% of adults) is 3.3. And with OECD average, strength of legal rights index is 6.8, depth of credit information index is 4.9, public registry coverage (% of adults) is 8.8, and private bureau coverage (% of adults) is 59.6. Note that the Legal Rights Index ranges from 0-10, with higher scores indicating that those laws are better designed to expand access to credit. The Credit Information Index measures the scope, access and quality of credit information available through public registries or private bureaus. It ranges from 0-6, with higher values indicating that more credit information is available from a public registry or private bureau.

In protecting investors, extent of disclosure index is 6, extent of director liability index is 1, ease of shareholder suits index is 9, and strength of investor protection index is 5.3. Compare this with South Asia: extent of disclosure index is 4.3, extent of director liability index is 4.3, ease of shareholder suits index is 6.4, and strength of investor protection index is 5. And with OECD average, extent of disclosure index is 5.9, extent of director liability index is 5, ease of shareholder suits index is 6.6, and strength of investor protection index is 5.8. Note that the indicators above describe three dimensions of investor protection: transparency of transactions (Extent of Disclosure Index), liability for self-dealing (Extent of Director Liability Index), shareholders’ ability to sue officers and directors for misconduct (Ease of Shareholder Suits Index) and Strength of Investor Protection Index. The indexes vary between 0 and 10, with higher values indicating greater disclosure, greater liability of directors, greater powers of shareholders to challenge the transaction, and better investor protection.

In paying taxes, an entrepreneur have to make 34 payments per year, spend 338 hours per year preparing tax stuff, pays 16.8 percent tax on profits, labor tax and contributions equal to 11.3 percent, other taxes equal to 10.7 percent and total tax rate is 38.8 percent of profit. Compare with South Asia: an entrepreneur have to make 31.3 payments per year, spend 284.5 hours per year preparing tax stuff, pays 17.9 percent tax on profits, labor tax and contributions equal to 7.8 percent, other taxes equal to 14.2 percent and total tax rate is 40 percent of profit. Compare with OECD average: an entrepreneur have to make 12.8 payments per year, spend 194.1 hours per year preparing tax stuff, pays 16.1 percent tax on profits, labor tax and contributions equal to 24.3 percent, other taxes equal to 4.1 percent and total tax rate is 44.5 percent of profit.

In trading across borders, it takes 9 documents, 41 days, and costs US$ 1764 per container to export a standardized shipment of goods. Meanwhile, it takes 10 documents, 35 days, and US$ 1825 to import a standardized shipment of goods. Compare this with South Asia: it takes 8.5 documents, 32.4 days, and costs US$ 1364.1 per container to export a standardized shipment of goods, while it takes 9 documents, 32.2 days, and US$ 1509.1 to import a standardized shipment of goods. And with OECD average: it takes 4.3 documents, 10.5 days, and costs US$ 1089.7 per container to export a standardized shipment of goods, while it takes 4.9 documents, 11 days, and US$ 1145.9 to import a standardized shipment of goods.

In enforcing contracts (commercial), it takes 39 procedures, 735 days, and costs 26.8 percent of claim. Compare this with South Asia: it takes 43.5 procedures, 1052.9 days, and costs 27.2 percent of claim. And with OECD average: it takes 30.6 procedures, 462.4 days, and costs 19.2 percent of claim.

In closing a business (resolve bankruptcies), it takes 5 years, costs 9 percent of estate and recovery rate is 24.5 cents on the dollar (claimants recover from the insolvent firm). Compare with South Asia: it takes 4.5 years, costs 6.5 percent of estate and recovery rate is 20.4 cents on the dollar. And with OECD average: it takes 1.7 years, costs 8.4 percent of estate and recovery rate is 68.6 cents on the dollar.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Nepal to cap CEO’s pay

Nepal’s central bank has decided to cap CEO’s pay to eight to 10 percent of total expenses made on employees of their respective institutions.

[…] a ceiling on the salary and benefits of CEOs was needed to check existing practice of handing out huge amount of perks and benefits to the head honchos, even if the financial condition of the bank concerned is not very sound. Similarly, the huge pay has been used by some executives cum promoters to “quietly” recoup their investment, in the form of remuneration.

The NRB study also concluded that the practice of awarding huge pay to the CEOs and other subordinates was also putting pressure on the management, especially of new banks, to increase earnings by many folds to pay the increased liabilities. This often instigates the management to make massive risky investment in unproductive sectors like land and real estate that are rejected by established banks, said the official.

Sounds good to reduce malpractices in the (bubbling) banking sector and to decrease widening income inequality!

Are economists to blame for the crisis?

Yes, says Krugman. But the economists he is talking about are neoclassicals and their variants, who have been pretty much driving economics and economic policy for a long time. He argues that the neoclassical stuff is neat and clean but wrong and its alternative is messier and not straight forward but right.

one thing’s for sure: we don’t have that beautiful final theory now, so the current choice is between ideas that are beautiful but wrong and a much messier hodgepodge.

Here is how he feels about economics, economists, and the whole profession. This is a good rundown of the trouble with economics and economists for people how have not read Krugman’s book ‘The Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008’, which I have reviewed here.

Few economists saw our current crisis coming, but this predictive failure was the least of the field’s problems. More important was the profession’s blindness to the very possibility of catastrophic failures in a market economy. During the golden years, financial economists came to believe that markets were inherently stable — indeed, that stocks and other assets were always priced just right. There was nothing in the prevailing models suggesting the possibility of the kind of collapse that happened last year. Meanwhile, macroeconomists were divided in their views. But the main division was between those who insisted that free-market economies never go astray and those who believed that economies may stray now and then but that any major deviations from the path of prosperity could and would be corrected by the all-powerful Fed. Neither side was prepared to cope with an economy that went off the rails despite the Fed’s best efforts.

And in the wake of the crisis, the fault lines in the economics profession have yawned wider than ever. Lucas says the Obama administration’s stimulus plans are “schlock economics,” and his Chicago colleague John Cochrane says they’re based on discredited “fairy tales.” In response, Brad DeLong of the University of California, Berkeley, writes of the “intellectual collapse” of the Chicago School, and I myself have written that comments from Chicago economists are the product of a Dark Age of macroeconomics in which hard-won knowledge has been forgotten.

As I see it, the economics profession went astray because economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth. Until the Great Depression, most economists clung to a vision of capitalism as a perfect or nearly perfect system. That vision wasn’t sustainable in the face of mass unemployment, but as memories of the Depression faded, economists fell back in love with the old, idealized vision of an economy in which rational individuals interact in perfect markets, this time gussied up with fancy equations. The renewed romance with the idealized market was, to be sure, partly a response to shifting political winds, partly a response to financial incentives. But while sabbaticals at the Hoover Institution and job opportunities on Wall Street are nothing to sneeze at, the central cause of the profession’s failure was the desire for an all-encompassing, intellectually elegant approach that also gave economists a chance to show off their mathematical prowess.

Unfortunately, this romanticized and sanitized vision of the economy led most economists to ignore all the things that can go wrong. They turned a blind eye to the limitations of human rationality that often lead to bubbles and busts; to the problems of institutions that run amok; to the imperfections of markets — especially financial markets — that can cause the economy’s operating system to undergo sudden, unpredictable crashes; and to the dangers created when regulators don’t believe in regulation.

It’s much harder to say where the economics profession goes from here. But what’s almost certain is that economists will have to learn to live with messiness. That is, they will have to acknowledge the importance of irrational and often unpredictable behavior, face up to the often idiosyncratic imperfections of markets and accept that an elegant economic “theory of everything” is a long way off. In practical terms, this will translate into more cautious policy advice — and a reduced willingness to dismantle economic safeguards in the faith that markets will solve all problems.

About Keynes:

Keynes did not, despite what you may have heard, want the government to run the economy. He described his analysis in his 1936 masterwork, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,” as “moderately conservative in its implications.” He wanted to fix capitalism, not replace it. But he did challenge the notion that free-market economies can function without a minder, expressing particular contempt for financial markets, which he viewed as being dominated by short-term speculation with little regard for fundamentals. And he called for active government intervention — printing more money and, if necessary, spending heavily on public works — to fight unemployment during slumps.

It’s important to understand that Keynes did much more than make bold assertions. “The General Theory” is a work of profound, deep analysis — analysis that persuaded the best young economists of the day. Yet the story of economics over the past half century is, to a large degree, the story of a retreat from Keynesianism and a return to neoclassicism. The neoclassical revival was initially led by Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago, who asserted as early as 1953 that neoclassical economics works well enough as a description of the way the economy actually functions to be “both extremely fruitful and deserving of much confidence.” But what about depressions?

[..] Eventually, however, the anti-Keynesian counterrevolution went far beyond Friedman’s position, which came to seem relatively moderate compared with what his successors were saying. Among financial economists, Keynes’s disparaging vision of financial markets as a “casino” was replaced by “efficient market” theory, which asserted that financial markets always get asset prices right given the available information. Meanwhile, many macroeconomists completely rejected Keynes’s framework for understanding economic slumps. Some returned to the view of Schumpeter and other apologists for the Great Depression, viewing recessions as a good thing, part of the economy’s adjustment to change. And even those not willing to go that far argued that any attempt to fight an economic slump would do more harm than good.

[…]“We have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle, having blundered in the control of a delicate machine, the working of which we do not understand. The result is that our possibilities of wealth may run to waste for a time — perhaps for a long time.” So wrote John Maynard Keynes in an essay titled “The Great Slump of 1930,” in which he tried to explain the catastrophe then overtaking the world. And the world’s possibilities of wealth did indeed run to waste for a long time; it took World War II to bring the Great Depression to a definitive end.

About faulty models:

[…] It’s hard to argue that this transformation in the profession was driven by events. True, the memory of 1929 was gradually receding, but there continued to be bull markets, with widespread tales of speculative excess, followed by bear markets. In 1973-4, for example, stocks lost 48 percent of their value. And the 1987 stock crash, in which the Dow plunged nearly 23 percent in a day for no clear reason, should have raised at least a few doubts about market rationality.

These events, however, which Keynes would have considered evidence of the unreliability of markets, did little to blunt the force of a beautiful idea. The theoretical model that finance economists developed by assuming that every investor rationally balances risk against reward — the so-called Capital Asset Pricing Model, or CAPM (pronounced cap-em) — is wonderfully elegant. And if you accept its premises it’s also extremely useful. CAPM not only tells you how to choose your portfolio — even more important from the financial industry’s point of view, it tells you how to put a price on financial derivatives, claims on claims. The elegance and apparent usefulness of the new theory led to a string of Nobel prizes for its creators, and many of the theory’s adepts also received more mundane rewards: Armed with their new models and formidable math skills — the more arcane uses of CAPM require physicist-level computations — mild-mannered business-school professors could and did become Wall Street rocket scientists, earning Wall Street paychecks.

To be fair, finance theorists didn’t accept the efficient-market hypothesis merely because it was elegant, convenient and lucrative. They also produced a great deal of statistical evidence, which at first seemed strongly supportive. But this evidence was of an oddly limited form. Finance economists rarely asked the seemingly obvious (though not easily answered) question of whether asset prices made sense given real-world fundamentals like earnings. Instead, they asked only whether asset prices made sense given other asset prices. Larry Summers, now the top economic adviser in the Obama administration, once mocked finance professors with a parable about “ketchup economists” who “have shown that two-quart bottles of ketchup invariably sell for exactly twice as much as one-quart bottles of ketchup,” and conclude from this that the ketchup market is perfectly efficient.

Saltwater economists vs. Freshwater economists:

Forty years ago most economists would have agreed with this interpretation. But since then macroeconomics has divided into two great factions: “saltwater” economists (mainly in coastal U.S. universities), who have a more or less Keynesian vision of what recessions are all about; and “freshwater” economists (mainly at inland schools), who consider that vision nonsense.

Freshwater economists are, essentially, neoclassical purists. They believe that all worthwhile economic analysis starts from the premise that people are rational and markets work, a premise violated by the story of the baby-sitting co-op. As they see it, a general lack of sufficient demand isn’t possible, because prices always move to match supply with demand. If people want more baby-sitting coupons, the value of those coupons will rise, so that they’re worth, say, 40 minutes of baby-sitting rather than half an hour — or, equivalently, the cost of an hours’ baby-sitting would fall from 2 coupons to 1.5. And that would solve the problem: the purchasing power of the coupons in circulation would have risen, so that people would feel no need to hoard more, and there would be no recession.

[…]Meanwhile, saltwater economists balked. Where the freshwater economists were purists, saltwater economists were pragmatists. While economists like N. Gregory Mankiw at Harvard, Olivier Blanchard at M.I.T. and David Romer at the University of California, Berkeley, acknowledged that it was hard to reconcile a Keynesian demand-side view of recessions with neoclassical theory, they found the evidence that recessions are, in fact, demand-driven too compelling to reject. So they were willing to deviate from the assumption of perfect markets or perfect rationality, or both, adding enough imperfections to accommodate a more or less Keynesian view of recessions. And in the saltwater view, active policy to fight recessions remained desirable.

But the self-described New Keynesian economists weren’t immune to the charms of rational individuals and perfect markets. They tried to keep their deviations from neoclassical orthodoxy as limited as possible. This meant that there was no room in the prevailing models for such things as bubbles and banking-system collapse. The fact that such things continued to happen in the real world — there was a terrible financial and macroeconomic crisis in much of Asia in 1997-8 and a depression-level slump in Argentina in 2002 — wasn’t reflected in the mainstream of New Keynesian thinking.

Even so, you might have thought that the differing worldviews of freshwater and saltwater economists would have put them constantly at loggerheads over economic policy. Somewhat surprisingly, however, between around 1985 and 2007 the disputes between freshwater and saltwater economists were mainly about theory, not action. The reason, I believe, is that New Keynesians, unlike the original Keynesians, didn’t think fiscal policy — changes in government spending or taxes — was needed to fight recessions. They believed that monetary policy, administered by the technocrats at the Fed, could provide whatever remedies the economy needed. At a 90th birthday celebration for Milton Friedman, Ben Bernanke, formerly a more or less New Keynesian professor at Princeton, and by then a member of the Fed’s governing board, declared of the Great Depression: “You’re right. We did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, it won’t happen again.” The clear message was that all you need to avoid depressions is a smarter Fed.

And as long as macroeconomic policy was left in the hands of the maestro Greenspan, without Keynesian-type stimulus programs, freshwater economists found little to complain about. (They didn’t believe that monetary policy did any good, but they didn’t believe it did any harm, either.)

It would take a crisis to reveal both how little common ground there was and how Panglossian even New Keynesian economics had become.

[…] saltwater economists, who had comforted themselves with the belief that the great divide in macroeconomics was narrowing, were shocked to realize that freshwater economists hadn’t been listening at all. Freshwater economists who inveighed against the stimulus didn’t sound like scholars who had weighed Keynesian arguments and found them wanting. Rather, they sounded like people who had no idea what Keynesian economics was about, who were resurrecting pre-1930 fallacies in the belief that they were saying something new and profound.

[…] Why should it take mass unemployment across the whole nation to get carpenters to move out of Nevada? Can anyone seriously claim that we’ve lost 6.7 million jobs because fewer Americans want to work? But it was inevitable that freshwater economists would find themselves trapped in this cul-de-sac: if you start from the assumption that people are perfectly rational and markets are perfectly efficient, you have to conclude that unemployment is voluntary and recessions are desirable.

Keynesian fiscal stimulus:

During a normal recession, the Fed responds by buying Treasury bills — short-term government debt — from banks. This drives interest rates on government debt down; investors seeking a higher rate of return move into other assets, driving other interest rates down as well; and normally these lower interest rates eventually lead to an economic bounceback. The Fed dealt with the recession that began in 1990 by driving short-term interest rates from 9 percent down to 3 percent. It dealt with the recession that began in 2001 by driving rates from 6.5 percent to 1 percent. And it tried to deal with the current recession by driving rates down from 5.25 percent to zero.

But zero, it turned out, isn’t low enough to end this recession. And the Fed can’t push rates below zero, since at near-zero rates investors simply hoard cash rather than lending it out. So by late 2008, with interest rates basically at what macroeconomists call the “zero lower bound” even as the recession continued to deepen, conventional monetary policy had lost all traction.

Now what? This is the second time America has been up against the zero lower bound, the previous occasion being the Great Depression. And it was precisely the observation that there’s a lower bound to interest rates that led Keynes to advocate higher government spending: when monetary policy is ineffective and the private sector can’t be persuaded to spend more, the public sector must take its place in supporting the economy. Fiscal stimulus is the Keynesian answer to the kind of depression-type economic situation we’re currently in.

What needs to change?

So here’s what I think economists have to do. First, they have to face up to the inconvenient reality that financial markets fall far short of perfection, that they are subject to extraordinary delusions and the madness of crowds. Second, they have to admit — and this will be very hard for the people who giggled and whispered over Keynes — that Keynesian economics remains the best framework we have for making sense of recessions and depressions. Third, they’ll have to do their best to incorporate the realities of finance into macroeconomics.

Many economists will find these changes deeply disturbing. It will be a long time, if ever, before the new, more realistic approaches to finance and macroeconomics offer the same kind of clarity, completeness and sheer beauty that characterizes the full neoclassical approach. To some economists that will be a reason to cling to neoclassicism, despite its utter failure to make sense of the greatest economic crisis in three generations. This seems, however, like a good time to recall the words of H. L. Mencken: “There is always an easy solution to every human problem — neat, plausible and wrong.”

When it comes to the all-too-human problem of recessions and depressions, economists need to abandon the neat but wrong solution of assuming that everyone is rational and markets work perfectly. The vision that emerges as the profession rethinks its foundations may not be all that clear; it certainly won’t be neat; but we can hope that it will have the virtue of being at least partly right.

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Thoughts on Paul Mason’s book ‘The End of the Age of Greed’

I just finished reading Paul Mason’s book Meltdown: The End of The Age of Greed. I found the book very informative and enriching. While reading the book, sometimes you feel that the blame for the whole financial crisis should be heaped upon the corporate elites and the policymakers, who aided elite’s greedy nature in order to fulfill their own greed. The nexus between the corporate elites, who only cared about increasing profits and dividends by often going roundabout laws and lobbying for easier rules, and politicians who shared similar ideology (economic) in principal was something much deeper than what I had imagined.

He walks readers through events like the repealing in 1999 of Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 in the US and the wave of deregulation (propounded by conservative policymakers by flowing with the partisan findings of conservative think tanks, which are funded by the business community that have vested interested in profit- making only), separating investment banking from regulation, allowing the sub-prime market to deliberately bloat, giving derivatives markets to free ride without supervision, and a deep-rooted belief on a flawed ideology (to borrow Krugman’s words “crank philosophy”) among others, all of which contributed to the global financial crisis.

Mason offers a fairly detailed timeline and description of the events that occurred during the makeup to and after the crisis. I will briefly note and quote the stuff I find interesting in the book.This blog post is not a review of his book.

In human terms, the commodities craze was the shortest, steepest and most disastrous of the bubbles. If subprime ruined the credit scores of millions of Americans, the commodity inflation took food out of the mouths of mouths of children from Haiti to Bangladesh, and made many middle-income people in the developed world feel instantly poor. [...] G7 politicians generally tried to address the combined credit freeze and commodity inflation with the old tools and the old obsession. The inflation hawks fought inflation; the monetarists flooded the system with money; fiscal conservatives attacked government profligacy. And economists, consulting their graphs, saw the end of a cycle instead of the end of an era.

He argues that the credit freeze and commodity prices boom originated in the parts of the financial system that were impenetrable to public scrutiny. The derivatives market had no surveillance despite it being about six folds the size of global real GDP. Similar was the case with credit default swaps, whose market was valued at $58 trillion. He believes that a blind belief in neoliberal ideology, which is focused too much on self-interest and self-regulation, is partly the cause of this crisis.

Neoliberalism, like all ideologies, needs to be understood exactly as it wishes to avoid being understood: as the product of history. [...] Neoliberalism fought its way to dominance against the power of the Keynesian establishment: against Nixon, Carter, Callaghan; against the Marxist and Keynesian influence in the academia. Above all it was a doctrine of conflict and vision. [...] The problem with neoliberalism's critics, for now, is that they have no coherent world view to take its place. There are elements of such a world view, scattered within the writings of neo-Keynesians, the anti-globalisation left and the Stiglitz critique of neoliberalism.

He maintains that information technology has shaped our lives and lifestyles beyond what we could imagine. This, along with political changes and heavily funded conservative think tanks, has also accelerated the adoption of neoliberal ideas across the society.

It is too crude to say the silicon chip 'causes' the rise of the free market, globalisation and finance capitalism. But the silicon chip and the internet protocol were surely key to their rapid rise to dominance.

He gives details of works of two economists who more or less predicted periodic booms and busts in the market. First, he talks about Kondratiev wave, a path first described by Russian economist Nikolai Kondrative. It predicts that capitalism moves through, on average, fifty-year cycles in which periods of economic growth are followed by periods of crisis and then depression. This theory explains the booms and busts except for the period after 80s and 90s, when the gold standard was abandoned, central banks developed new measures to expand credit and tame inflation, and the Berlin Wall fell down.

He then talks about Hyman Minsky, who laid out the reasoning and tools to predict the crisis and recommended how to resolve it. Minsky argues that capitalist society is inherently flawed and when it is uncontrolled, the government has to step in to remedy the uncontrolled aspects. He warned, "The normal functioning of our economy leads to financial trauma and crises, inflation, currency depreciation, unemployment and poverty in the midst of what could be virtually universal affluence- in short ... financially complex capitalism is inherently flawed." We need to live with the fact that capitalism is flawed; it is not perfect and efficient; and policymakers can use policy tools to mitigate the effects of downsides of capitalism.

Minsky's proposed solution to financial crisis (which is more or less is close to what Krugman and other Keynesian economists have been rightly saying):

... state intervention in two fronts: the government should run a big budget and the central bank should pump money into the economy. It will be noted, despite Minsky's pariah status in economics, that his remedy is exactly what has been adopted- in the US, the UK, the eurozone and much of the developed world. The problem is, it has not so far worked. Trillions of dollars of ready money, tax cuts and state spending were shoveled into the world economy to stop the credit crunch producing another Great Depression. yet all those trillions are up against a powerful backwash of collapse within the real economy.

I think Mason is misguided here and is taking a very short-sighted view about the impact of stimulus. First, the global fiscal stimulus is just above a trillion dollars and is not expected to kick in until early 2010. Second, the fiscal stimulus was small if we look at the historic nature of this slump. In the US economy, Krugman has been calling for a stimulus equivalent to 4 percent of GDP, which is not politically feasible though it would have been the best policy move if enacted. The global economy needs to be heated (because the economy still is slightly close to deflationary point) and slight inflation with budget deficit must be tolerated. In fact, the global economy, especially the emerging Asia and some EU nations, have rebounded from the first quarter of 2009. So, the fiscal stimulus (clearly worked in China, France, Germany, Australia) along with liquidity injection from the central banks have worked for now. It needs to be seen if the current nascent recovery is sustainable.

Mason outlines three rational alternatives for the developed world: (i) revive the high-debt/low-wage model under the more controlled conditions (pretty much the one agreed by G20); (ii) abandon high growth as an objective altogether; (iii) a return to higher wages, redistribution and a highly regulated finance system. The third one is close to what Minsky argued for-- a high-growth economy that transcends the limitations of both Keynesian and neoliberal models (nationalization/semi-nationalization of banking and insurance industries; strict limits on speculative finance; address inequality by changing tax structure so that the bottom half of the income scale benefit from growth; and consumer demand sustained by growth itself; create permanently benign conditions for entrepreneurs by limiting the power of large-scale enterprises).

On a side note, I think Mason does not fully explore Sachs’ prescribed "shock therapy" that created mess during Russia’s transformation from socialist to capitalist economy. He is favorable of Sachs and wrongly attributes some of the events to Sachs’s academic and policy activism. That said, he does mention the role played by Sachs, and Stiglitz, in making policymakers aware that the IMF-prescribed policies to East Asia after the 1997 crisis was flawed.

He thinks that the Minsky model would be the likely outcome because of heavy government involvement in the market (as was necessitated by the mess created by the markets):

As the crises worsens, it is becoming commonplace for pundits to observe, while capitalism is collapsing, that nobody has thought of an alternative. This is not true. The Minsky alternative- a socialised banking system plus redistribution- is, I believe, the ground on which the most radical of the capitalist re-regulators will coalesce with social justice activists. And it may even go mainstream if the only alternative is seen to be low growth, decades of debt-imposed stagnation, or another re-run of this crisis a few years down the line. It is also possible that a socialised banking system, by allowing the central allocation of financial resources, could be harnessed to the rapid development and large-scale production of post-carbon technologies.

Overall, a very good and informative book about the meltdown. John Kay reviews Mason's book here.