Dani Rodrik gives a feel about what the scale of the present financial crisis would be in the emerging countries. He thinks that the emerging countries would face much more severe crisis than the developed counterparts.

Emerging markets for the most part have weak and fragile fiscal systems, and the magnitude of the potential run is huge relative even to the large mountains of reserves that many of them have built up. Socialization of private liabilities may enhance confidence in the rich countries; it will likely magnify the run in emerging markets. So we are talking about economic collapses that could be significantly bigger than what the rich countries will experience. And this time developing countries can legitimately say: it wasn't our fault!

It would be interesting to know what new ideas transpired/were floated when Rodrik, Rogoff, Stiglitz, Birdsall, and Sachs met with the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon recently. Rodrik sees a possible role for the IMF as a true global lender (massive) of last resort (without too many preconditions).

On a similar note, here is an interesting perspective: From capital flow bonanza to financial crash:

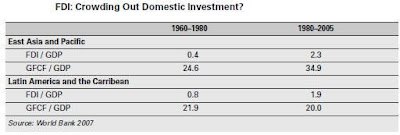

To examine the potential links with financial crises of various stripes, we constructed a family of country-specific probabilities. For each of the 64 countries, this implies four unconditional crisis probabilities, that of: default (or restructuring) on external sovereign debt, a currency crash, and a banking crisis. We also constructed the probability of each type of crisis within a window of three years before and after the bonanza year or years, this we refer to as the conditional probability of a crisis. If capital flow bonanzas make countries more crises prone, the conditional probability should be greater than the unconditional probability of a crisis.

For the full sample, the probability of any of the three varieties of crises conditional on a capital flow bonanza is significantly higher than the unconditional probability. Put differently, the incidence of a financial crisis is higher around a capital inflow bonanza. However, separating the high income countries from the rest qualifies the general result. As for the high income group, there are no systematic differences between the conditional and unconditional probabilities in the aggregate, although there are numerous country cases where the crisis probabilities increase markedly around a capital flow bonanza episode.

For sovereign defaults, less than half the countries (42%) record an increase in default probabilities around capital flow bonanzas. (Here, it is important to recall that about one-third of the countries in the sample are high income.) In two-thirds of the countries the likelihood of a currency crash is significantly higher around capital flow bonanzas in about 61% of the countries the probability of a banking crises is higher around capital flow bonanzas.

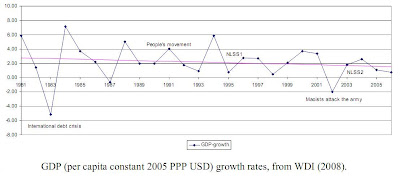

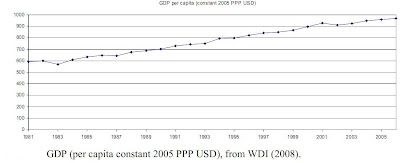

Most emerging market economies have thus far been relatively immune to the slowdown in the US. Many are basking in the economic warmth provided by high commodity prices and low borrowing costs. If the pattern of the past few decades holds true, however, those countries may be facing a darkening future.