An interesting compilation of the most interesting events and news of 2010 compiled by FT’s Tim Harford. Here is a rundown, by the FT team, of the major expected events in 2011.

An interesting compilation of the most interesting events and news of 2010 compiled by FT’s Tim Harford. Here is a rundown, by the FT team, of the major expected events in 2011.

My last op-ed for this year! It is about Nepal’s industrial and export interests in the upcoming Doha Round of trade negotiations under the WTO. I outline what Nepal’s interests are, what it should do, and why it should align with the LDCs in trade negotiations.

Amidst the euphoria and repeated interaction between ministry officials and businessmen regarding cash incentives on exports, there is a different storm brewing, albeit quietly, in the international trade regime. Trade analysts and representatives in other countries are gearing up to outline country agenda for the next Doha Round (DR) of trade negotiations under the WTO. While they are working on ensuring the reflection of their domestic industrial and export interests in the upcoming trade negotiations, and possibly a passage of the DR, Nepali bureaucrats, industrialists and exporters are running after cash incentives on exports. They seem to be oblivious and unbothered by declining exports competitiveness and our national agenda for the next round of trade negotiations.

In 2011, the DR will dominate trade talks globally. Unfortunately, our bureaucrats and business community are unprepared for this. They are oblivious of our industrial and export interests and how to include them in common agenda of Least Developed Countries (LDCs).Their unpreparedness and halfhearted engagement in trade talks should not be surprising. Precisely because of this, since Nepal joined the WTO on April 23, 2004, becoming the first LDC to join the trading bloc through full working party negotiation process, its exports performance has been very disappointing.

For starters, Doha Round, which started in November 2001, is the ongoing trade negotiation round that aims to lower trade barriers globally. Multiple rounds of negotiations failed because of disagreement over agricultural subsidies in the US and the EU, industrial tariffs and non tariff barriers, services and special trade measures. The latest negotiation broke down due to India’s insistence on the inclusion of special safeguard mechanism (SSM), a measure designed to protect poor farmers by allowing countries to impose tariff on certain agricultural goods in case of rapid price volatility. Though it is believed that the developing countries would benefit from the passage of the DR, various studies show only a handful of countries would reap the benefits.

Not only do we don’t know the developmental impact of the DR, we also have no clue how specifically it will aid Nepal’s industrial and export sectors. The most reasonable estimates show that Nepal would see meager gains. A World Bank study showed that total gains from the DR would be as low as $96 billion and only $16 billion would go to developing countries. Worse, half of all the benefits that would go to the developing countries would be reaped by just eight countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Mexico, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam). For South Asia, real income gains would be about US$2.5 billion. India alone is expected to gain US$ 1.7 billion. That leaves US$ 0.8 billion for the rest of South Asia. It shows that there is very little gains at store for Nepal. Worse, terms of trade, the relative prices of a country’s export to import, is expected to worsen, putting further strain on exports and hurting net food importer LDCs like Nepal. Additionally, another study by Carnegie Endowment shows that total gains from trade would be even lower (between US$ 32-55 billion) than the WB’s estimate, with rich nations getting $30 billion; middle income countries like China, Brazil and South Africa getting $20 billion; and poor countries getting $5 billion (about $2 per head).

Even if the gains are meager, Nepal should not ignore multilateral trade negotiations. We should not be a mute spectator during trade negotiations. It should actively support LDCs’ agenda. That way it can reap benefits offered to all LDCs plus lobby for special measures to ramp up our industrial and export sectors.

Nepal should be pushing for the inclusion of its industrial and trade interests in LDCs’ common agenda. Since a substantial portion of our trade happens with our neighbors, our bureaucrats and negotiators, while supporting LDCs’ agenda, should also push for special concessions such as greater transit rights and non tariff barriers to landlocked LDCs. Pushing for favorable trade measures to exploit regional markets is in our national interest. It will further help penetrate regional markets, where the transaction and transportation costs related to trade are lower than in the EU and the US. Mind you, the latter markets are also important, but all LDCs will have uniform privileges in these markets. Nepal needs those privileges plus greater preferences in the regional markets, where trade complementarities are pretty high.

There are a few LDCs’ agenda that Nepal should support. First, seeking duty-free, quota free (DFQF) trade commitment on all products is in both Nepal’s and LDCs’ interests. The developed countries should agree to this even before the DR negotiations begin next year. It will show seriousness of the developed countries in creating a more liberal trade regime than the existing one, and assure other countries that protectionist measures, especially after the global economic crisis, will not cloud over progress made so far in multilateral trade regime. Since DFQF on all products would erode marginal preference enjoyed by some developing countries, Nepal should also push for securing some sort of marginal preference, over and above DFQF applicable to all LDCs. This could come in the form of low non tariff barriers and relaxed rules of origin for market assess in key regional and nonregional destinations. These are needed to sustain our exports given its existing level of low product sophistication and diversification. Furthermore, convincing and winning India’s confidence in our trade structure and system is in our long term national interest regarding industrial, export and economic growth.

Second, Nepal should also confirm to LDCs’ agenda on “bio-piracy”, which is the use of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge without benefit sharing and prior consent. Nepal should push for full disclosure on the use of bio products native to a certain indigenous group, community or country. Third, on issues of intellectual property rights (IPR), especially concerning patent on medicines secured by western multinational pharmaceutical companies, Nepal should back LDCs’ agenda that such patents should not compromise on public health needs of the developing countries.

Fourth, regarding Aid for Trade (AfT), it is in our interest to seek adequate, reliable, and predictable funding for not only developing human resources and technical aspects of trade, but also concrete aspects such as funds for the construction of infrastructures along major trading routes. For instance, allocating meager sum of money for building awareness and technical capacity regarding trademarks and packaging will do little to overcome supply side constraints such as lack of roads, electricity, communication and storage facilities. Ensuring the latter would directly aid trade, employment and growth. Note that sometimes for small and medium enterprises, which are the mainstay of our economy, the cost of protecting trademark at the global level is higher than the total revenue generated from sales of such products. Nepal should push for a special facility whereby funds are available to fight trademark breaches in the international market.

Nepal needs smart bureaucrats and negotiators to not only fully understand both domestic and multilateral trade agendas, but also the art of successfully pushing for the inclusion of purely domestic industrial and export interests in the common agenda of LDCs. Along with largely confirming with the position of LDCs for the upcoming DR negotiations, Nepal should also seek greater preference, concession and market access, especially in the regional markets, where it has relatively higher competitive advantage than in the nonregional markets.

[Published in Republica, December 26, 2010, p.6]

Dutta, Howes and Murgai argue that unconditional cash transfers for the elderly and widows (pension schemes) in Karnataka and Rajasthan worked due to small size and relatively low level of leakage. Regarding scaling-up of the project, the authors caution that the outcome would depend on the likely impact of increased coverage on both targeting and leakage. They argue that increased coverage would most likely worsen targeting. Currently, leakages are low because levels of discretion are low. As program expands, avenues for leakages (bribes, diversion of funds) will be higher.

If the program is to be expanded, then the authors suggest:

In the short term, the way forward would be to expand the coverage among widows and the elderly and to increase the size of the pension. This is a path the Government of India has already embarked upon. In the longer term, the policy question is whether it makes a sense to expand the categories to whom social pensions are given.

Ultimately, one can imagine a situation in which, say, cash pensions are made to every holder of a BPL card, instead of, or as well as, an entitlement to buy subsidised food and/or to a guarantee to a minimum number of days of public employment. With the National Right to Employment Guarantee Act, and the decision of the government to support a Right to Food Act such a scenario is far-fetched today. Moreover, as stressed above, little is known about how cash transfers would perform if scaled up. Nevertheless, it is reassuring to know that calls for a greater role in Indian social security policy for cash transfers are at least not contradicted by the performance of India’s existing cash transfers.

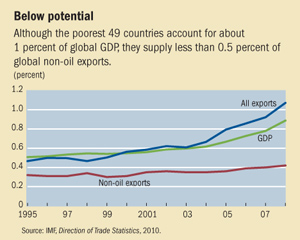

Adapted from Katriin Elborgh-Woytek and Robert Gergory’s piece in the latest edition of IMF’s Finance & Development magazine.

There are steps the poorest economies themselves could take to boost exports—such as reducing the often prevailing antitrade bias in their trade, tax, customs, and exchange rate regimes; issuing more transparent trade and customs regulations; and taking steps to improve such key service sectors as communications and transportation (see World Bank, 2010).

But the poorest exporting economies would benefit considerably if emerging as well as advanced economies gave them better opportunities for trade, which would improve their growth and productivity prospects (see Elborgh-Woytek, Gregory, and McDonald, 2010). There are a number of steps better-off countries could take to boost poor economies’ export potential. Some of them are well known to policymakers—in particular, concluding the current World Trade Organization (WTO) trade-negotiation talks, known as the Doha Round. Wide-ranging multilateral trade liberalization could spur growth and foster secure and open global trading. Poorer countries would gain from successful Doha Round conclusion through better access to advanced and emerging export markets.

But the poorest exporting economies would benefit considerably if emerging as well as advanced economies gave them better opportunities for trade, which would improve their growth and productivity prospects (see Elborgh-Woytek, Gregory, and McDonald, 2010). There are a number of steps better-off countries could take to boost poor economies’ export potential. Some of them are well known to policymakers—in particular, concluding the current World Trade Organization (WTO) trade-negotiation talks, known as the Doha Round. Wide-ranging multilateral trade liberalization could spur growth and foster secure and open global trading. Poorer countries would gain from successful Doha Round conclusion through better access to advanced and emerging export markets.

Although broad-based multilateral trade liberalization is the ultimate policy target, there are less-obvious intermediate avenues—such as the extension and improvement of duty-free and quota-free (DFQF) trade preferences both by advanced and emerging economies—that could add nearly $10 billion a year to the coffers of poorer economies. These preference systems are designed to offset for the poorest countries some of the high trade barriers in sectors such as light manufacturing and agriculture—areas in which LDCs are likely to export.

There are three main avenues for the more advanced and emerging economies to help integrate LDCs into the global economy:

If all exports from developing countries were exempt from tariffs and quotas, LDC exports to both advanced and emerging markets would grow significantly—on the order of $10 billion a year, or about 2 percent of their combined GDP (Laborde, 2008; and Bouët and others, 2010). Broadening the coverage of preferences by major advanced markets could generate increased exports from LDCs of about $2.2 billion a year, or about 6 percent of net official development assistance from industrial countries to LDCs. The potential increase is even larger for exports to emerging markets—about $7 billion a year in additional exports (Bouët and others, 2010). Although the positive impact on LDCs would be sizable, the negative effect on advanced and emerging economies would be tiny because of the low level of LDC exports.

Second, if better-off economies were to make rules of origin more flexible, LDCs would benefit too. Rules of origin determine whether a good “originates” in a country that benefits from a preference system. The rules specify the minimum amount of economic activity that must be undertaken in the country benefiting from the preference and whether inputs from other countries count toward this minimum. Rules of origin differ widely across countries’ preference programs. They are frequently based on the amount of value added in the preference-eligible country or on the transformation a good undergoes in that country (measured by a change in tariff classification). These rules strongly influence where an LDC buys its inputs, which affects the overall economic consequences of a preference program.

To qualify for a preference program, LDC exporters must often limit input sourcing to suppliers in their own country or those from the country granting the preference—even if it would be cheaper to buy inputs elsewhere. This can be difficult for less-diversified LDCs, which depend on intermediate goods, processes, or patents from other countries. Rules of origin can also be a source of distortion, if exporters turn to less-efficient, more costly input sources to qualify for preferences. Moreover, the administrative burden of meeting complex rules of origin can be substantial, costing as much as 3 percent of export value (Hoekman and Özden, 2005). As a result, perhaps a quarter to a third of eligible imports do not gain preference, and some trade that might have benefited from better-designed preferences is likely never undertaken.

More liberal rules of origin allow producers to source inputs flexibly. Such rules implicitly acknowledge LDCs’ low capital intensity and lack of horizontal or vertical integration. Under China’s preference program, for example, origin (and thus preference benefits) can be conferred on a product based either on a minimum local value-added threshold or a change in tariff classification—implicit acknowledgment that the product is different and the LDC has added value. India’s low 30 percent value-added threshold gives potential LDC exporters flexibility in sourcing their inputs.

Moreover, better-off countries could make it even easier to stimulate trade among LDCs if their rules of origin specifically allowed preference-eligible countries to buy inputs from other preference-eligible countries. If these so-called cumulation provisions allowed inputs from two or more countries to be counted together, it would make it easier for the preference-eligible country to meet the minimum requirements under the rules of origin. In contrast, narrow or restrictive cumulation provisions rules do not allow the use of inputs from other countries, often fragmenting established cross-border production relationships. Cumulation provisions therefore determine how easily preference beneficiaries can trade among themselves, using intermediate goods or processes that originate in other countries.

Permitting wider cumulation would assuredly mean that LDCs could meet the rules of origin more easily and at lower cost and would also encourage south-south trade. Allowing the poorest countries to source inputs from all LDCs and other developing countries while remaining eligible for preferences would provide the added flexibility needed for effective use of preference programs.

Negotiating the liberalisation of services is complicated. Adequate national regulation and international regulatory cooperation will often be necessary. A concerted effort is needed to help countries strengthen and improve service sector regulation and implementing institutions, as well as to cooperate with each other where there are significant regulatory externalities.

Much of what remains to be done to remove developing nation barriers to trade in services will be conditional on such regulatory improvements. An important element of any Doha package on services should therefore be agreement to create mechanisms to promote pro-competitive domestic regulatory reform and thus support liberalisation in the future.

Although comprehensive liberalisation of service markets in all 153 members in the Doha round is neither possible nor at this point in time desirable, the largest services economies (a “G25”) can and should go further.

But the larger players may also need to pursue domestic regulatory reforms before opening up some services sectors to foreign competition, and will need to strengthen regulatory cooperation to facilitate trade in some services.A pre-commitment approach will allow such conditions to be put in place and ensure that there is an agreed timetable to open markets to greater competition. Explicitly recognising that services liberalisation cannot – and should not be – divorced from services regulation will do much to help harness the potential that trade agreements have to expand services trade and investment.

More on services trade and the Doha Round by Bernard Hoekman and Aaditya Matto here

Becoming a rich country requires the ability to produce and export commodities that embody certain characteristics. We classify 779 exported commodities according to two dimensions: (1) sophistication (measured by the income content of the products exported); and (2) connectivity to other products (a well-connected export basket is one that allows an easy jump to other potential exports). We identify 352 “good” products and 427 “bad” products. Based on this, we categorize 154 countries into four groups according to these two characteristics. There are 34 countries whose export basket contains a significant share of good products. We find 28 countries in a “middle product” trap. These are countries whose export baskets contain a significant share of products that are in the middle of the sophistication and connectivity spectra. We also find 17 countries that are in a “middle-low” product trap, and 75 countries that are in a difficult and precarious “low product” trap. These are countries whose export baskets contain a significant share of unsophisticated products that are poorly connected to other products. To escape this situation, these countries need to implement policies that would help them accumulate the capabilities needed to manufacture and export more sophisticated and better connected products.

Here is a paper by Felipe, Kumar and Abdon. Their analysis is based on Hidalgo et al. (2007) and Hausmann et al. (2007)’s concept of product space, which is an application of network theory that yields a graphical representation of all products exported in the world. Products are linked through lines that represent their proximity, defined as the conditional probability of exporting one products given that they also export the other one. Countries change their export mix by jumping to products that are nearby, in the sense that these other products use similar capabilities to those used by the products in which they excel (those products in which they have revealed comparative advantage [RCA]). A country’s position within the product space signals its capacity to expand to more sophisticated products, thereby laying the groundwork for future growth. Countries that export products that have few linkages with other products or countries that have not accumulated sufficient capabilities to jump to other products cannot generate sustained long-term growth.

The focus is on manufacture and export of sophisticated and better connected products (PRODY) so that structural transformation-- whereby the economy moves from traditional, low wage sector to sophisticated, high wage sector—takes place in the developing countries. Here is more on their ranking of countries based on an “index of opportunities”. Here is a blog about Nepal’s export sophistication. The basic idea behind the whole analysis is that what countries products and export determines who they are in the world. Countries with a more sophisticated export basket growth faster.

So how does structural transformation occur? Basically, the major determinant of a country’s comparative advantage, and its trade pattern, is the relative factor endowment. Changing comparative advantage based on factor accumulation dictates a country’s export basket. If prices are right for the various factors of production so that firms select the most appropriate techniques for production, then factor accumulation leads to factor price changes, leading to changes in the techniques of production. Countries growth by accumulating physical or human capital or by improving the way various factors of production are mixed (TFP). This brings about a change in the composition of export basket. So, structural transformation is the results of changes in underlying fundamentals such as education, financial resources, and overall productivity. That said, export diversification is not easy.

Those firms that engage in “self discovery” face cost of discovery, leading to a situation where there might be high social returns but high private costs. If new products discovery fails, then the firm incurs the cost. But, if it succeeds, then other enter the market following the discovery. This is where government intervention might be required to offset private costs if there is high social return from any venture. Similarly, export diversification requires large initial investments (high fixed costs), which the government should own up. The government could facilitate information and coordination externalities.

Here are few recommendations (adapted from the same paper) for countries with low product sophistication to escape “low-product trap” :

Following its opening to trade and foreign investment in the mid-1980s, Mexico’s economic growth has been modest at best, particularly in comparison with that of China. Comparing these countries and reviewing the literature, we conclude that the relation between openness and growth is not a simple one. Using standard trade theory, we find that Mexico has gained from trade, and by some measures, more so than China. We sketch out a theory in which developing countries can grow faster than the United States by reforming. As a country becomes richer, this sort of catch-up becomes more difficult. Absent continuing reforms, Chinese growth is likely to slow down sharply, perhaps leaving China at a level less than Mexico’s real GDP per working-age person.

Full paper by Kehoe and Ruhl here.

Here is an earlier post about why Mexico isn’t rich? Hanson argues that “Mexico’s underperformance is overdetermined”. Though faulty provision of credit, persistence of informality, control of key input markets by elites, continued ineffectiveness of public education, and vulnerability to adverse external shocks each may have a role in explaining Mexico’s development trajectory, we don’t yet know the relative importance of these factors for the country’s growth record, he asserts.

Despite having far more people in developing countries (in proportional terms) engaged in entrepreneurial activities, and having their entrepreneurial skills frequently and severely tested than those of their counterparts in the rich countries, why are these more entrepreneurial countries poorer, wonders Ha-Joon Chang. The answer lies in the poor’s inability to channel the individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship.

Many people believe that the lack of entrepreneurship is one of the main causes of poverty in developing countries. However, anyone who is from or has lived for a period in a developing country will know that developing countries are teeming with entrepreneurs. On the streets of poor countries, you will meet men, women, and children of all ages selling everything you can think of, and things that you did not even know could be bought—a place in the queue for the visa section of the American Embassy (sold to you by professional queuers), the right to set up a food stall on a particular corner (perhaps sold by the corrupt local police boss), or even a patch of land to beg from (sold to you by the local thugs).

In contrast, most citizens of rich countries have not even come near to becoming an entrepreneur. They mostly work for a company, doing highly specialized and narrowly specified jobs, implementing someone else’s entrepreneurial vision.

The upshot is that people are far more entrepreneurial in the developing countries

than in the developed countries. According to an OECD study, in most developing countries, 30-50 per cent of the non-agricultural workforce is self-employed (the ratio tends to be even higher in agriculture). In some of the poorest countries, the ratio of people working as one-person entrepreneurs can be way above that: 66.9 per cent in Ghana, 75.4 per cent in Bangladesh, and a staggering 88.7 per cent in Benin (see 1 under further reading). In contrast, only 12.8 per cent of the non-agricultural workforce in developed countries is self-employed. In some countries, the ratio does not even reach one in ten: 6.7 per cent in Norway, 7.5 per cent in the USA, and 8.6 per cent in France. So, even excluding the farmers (which would make the ratio even higher), the chance of an average developing country person being an entrepreneur is more than twice that for a developed country person (30 per cent versus 12.8 per cent). The difference is 10 times, if we compare Bangladesh with the USA (7.5 per cent versus 75.4 per cent). And in the most extreme case, the chance of someone from Benin being an entrepreneur is 13 times higher than the equivalent chance for a Norwegian (88.7 per cent versus 6.7 per cent).Collective nature of entrepreneurship

Our discussion so far shows that what makes the poor countries poor is not the lack of raw individual entrepreneurial energy, which they in fact have in abundance. It is their inability to channel the individual entrepreneurial energy into collective entrepreneurship.

Very much influenced by capitalist folklore, with characters like Thomas Edison and Bill Gates, and by the pioneering theoretical work of Joseph Schumpeter, our view of entrepreneurship is too much tinged by the individualistic perspective—entrepreneurship is what those heroic individuals with exceptional vision and determination do. However, if it ever was true, this view is becoming increasingly obsolete. In the course of capitalist development, entrepreneurship has become an increasingly collective endeavour.

To begin with, even those exceptional individuals like Edison and Gates became what they are only because they were supported by a whole host of collective institutions—the whole scientific infrastructure that enabled them to acquire their knowledge and also experiment with it; company law and other commercial laws that made it possible for them subsequently to build companies with large and complex organizations; educational systems that supplied highly trained scientists, engineers, managers, and workers that manned those companies; financial systems that enabled them to raise huge amounts of capital when they wanted to expand; patent and copyright laws that protected their inventions; easily accessible markets for their products, and so on.

Furthermore, in the richer countries, enterprises co-operate with each other a lot more than do their counterparts in poorer countries. For example, the dairy sectors in countries like Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany have become what they are today only because their farmers organized themselves, with state help, into co-operatives and jointly invested in processing facilities and export marketing. In contrast, the dairy sectors in the Balkan countries have failed to develop, despite quite a large amount of microcredit channelled into them, mainly because their dairy farmers tried to make it on their own. For another example, many small firms in Italy and Germany jointly invest in R&D and export marketing, which are beyond their individual means, through industry associations (helped by government subsidies), whereas typical developing country firms do not invest in these areas because there is not such a collective mechanism.

Even at the firm level, entrepreneurship has become highly collective in the rich countries. Today, few companies are managed by charismatic visionaries like Edison or Gates, but by professional managers. Writing in the mid twentieth century, Schumpeter was already aware of this trend, although he was none too happy about it. He observed that the increasing scale of modern technologies was making it increasingly impossible for a large company to be established and run by a visionary individual entrepreneur. Schumpeter predicted that the displacement of heroic entrepreneurs with what he called ‘executive types’ would sap the dynamism from capitalism and eventually lead to its demise.

We establish the following stylized facts: (1) Exports are characterized by Big Hits, (2) the Big Hits change from one period to the next, and (3) these changes are not explained by global factors like global commodity prices. These conclusions are robust to excluding extractable products (oil and minerals) and other commodities. Moreover, African Big Hits exhibit similar patterns as Big Hits in non-African countries. We also discuss some concerns about data quality. These stylized facts are inconsistent with the traditional view that sees African exports as a passive commodity endowment, where changes are driven mostly by global commodity prices. In order to better understand the determinants of export success in Africa we interviewed several exporting entrepreneurs, government officials and NGOs. Some of the determinants that we document are conventional: moving up the quality ladder, utilizing strong comparative advantage, trade liberalization, investment in technological upgrades, foreign ownership, ethnic networks, and personal foreign experience of the entrepreneur. Other successes are triggered by idiosyncratic factors like entrepreneurial persistence, luck, and cost shocks, and some of the successes occur in areas that usually fail.

Full paper by Easterly and Reshef here.

Developing countries lose between $20 billion and $40 billion each year to bribery, embezzlement, and other corrupt practices. Over the past 15 years only $5 billion has been recovered and returned.

More on the Asset Recovery Handbook 2010

Investment in infrastructure can raise productivity, boost growth, and help reduce poverty. And, lack of infrastructure has been one of the most binding constraints on growth in the developing countries. They need massive investments in infrastructure to connect markets, facilitate trade, reduce transaction and transportation costs, and to facilitate movement of goods and services, among others. But, how to get investment in infrastructure right? Here is brief piece on how to do that.

Lawrence Edward and Robert Z Lawrence argue that while AGOA helped Africa LDCs cope with the shock of the end of MFA and compete with strong performers like China, it also discouraged additional value-addition in assembly and stimulated the use of expensive fabrics that were unlikely to be produced locally. Meanwhile, China moved up the value chain and produced competitive goods.

Lesotho and other least developed African countries responded impressively to the preferences they were granted under the African Growth and Opportunities Act with a rapid increase in their clothing exports to the US. But this performance has not been accompanied by some of the more dynamic growth benefits that might have been hoped for. In this study we develop the theory and present empirical evidence to demonstrate that these outcomes are the predictable consequences of the manner in which the specific preferences might be expected to work.

The MFA (Multi-fiber Arrangement) quotas on US imports of textiles created a favorable environment for low value-added, fabric-intensive clothing production in countries with unused quotas by inducing constrained countries to move into higher quality products. By allowing the least developed African countries to use third country fabrics in their clothing exports to the US, AGOA provided additional implicit effective subsidies to clothing that were multiples of the US tariffs on clothing imports. Taken together, these policies help account for the program’s success and demonstrate the importance of other rules of origin in preventing poor countries from taking advantage of other preference programs.

But the disappointments can also be attributed to the preferences because they discouraged additional value-addition in assembly and stimulated the use of expensive fabrics that were unlikely to be produced locally. When the MFA was removed, constrained countries such as China moved strongly into precisely the markets in which AGOA countries had specialized. Although AGOA helped the least developed countries withstand this shock, they were nonetheless adversely affected. Preference erosion due to MFN reductions in US clothing tariffs could similarly have particularly severe adverse effects on these countries.

Thanks largely to the subsidy Malawi has had seven years of economic growth, based on agriculture, which has had a major impact on reducing poverty, helping to halve child mortality rates. For me the key point is the huge role a government subsidy like this can play in getting an economy back on its feet and in stimulating (rather than stifling) growth and poverty-reducing private sector development. For many who see government subsidies as anti-private sector this will be counterintuitive. But it is exactly the kind of heterodox approach that will be needed to deliver success in Africa and in other poor countries, where we should leave our economic theory at the door and instead focus on what works empirically.

The Dorward and Chirwa paper is in no doubt that the subsidy has been a significant success. It has led to significant increases in maize production and productivity, which in turn has contributed to ‘increased food availability, higher real wages, wider economic growth and poverty reduction.’ The contribution in the last season was an extra million tonnes of maize, doubling pre-subsidy production levels.

The study shows that some of the non-poor do indeed benefit from the subsidy and that it must be better targeted, for example to more to female-headed households. However, 65% of Malawi’s farmers received the subsidy, and this includes many of the poorest.

The cost to the Malawi government of the subsidy has been around 9% of government spending, or 3.5% of GDP. This is not a trivial amount but it is not unsustainable. In 2008/9 this increased dramatically to 16% of GDP due to the global spike in fertiliser prices, but this has now fallen back to its previous level.

This cost has to be set against two things; the macroeconomic benefits of the subsidy, and the costs to government and the macro-economy of the alternatives.

Low inflation, and strong GDP growth all contribute to government revenues and to lowering the cost of borrowing. The paper concludes that the economic impact of the subsidy has definitely been positive.

At the same time the government has avoided having to make any costly food imports as it had to in the years immediately preceding the subsidy. As a land-locked country food imports are very expensive. The fertiliser subsidy enables farmers to grow more of their own food rather than rely on imported handouts in an increasingly volatile global market. One tonne of imported maize can support 5 families for 96 days, whereas the same sum of money spent on fertiliser could enable them to produce enough food for 10 months.

Whilst use of inorganic fertiliser is in one way environmentally unsound, Malawi’s emissions are near the bottom of the table. And by reducing the risk farmers face with an increasingly variable climate, the subsidy is a large scale adaptation strategy; effectively a form of insurance and stability for farmers that increases their resilience. Lastly by increasing the fertility of existing land, the subsidy helps combat deforestation and soil erosion from increasing use of marginal lands.

Summary of Dorward and Chirwa’s paper by Max Lawson.

Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian argue that food aid is determined by recipient country’s food shortages. But, food aid from some of the largest donors is the least responsive to production shocks in recipient countries. Also, food aid usually goes to counties with colonial ties.

We examine the supply-side and demand-side determinants of global bilateral food aid shipments between 1971 and 2008. First, we find that domestic food production in developing countries is negatively correlated with subsequent food aid receipts, suggesting that food aid receipt is partly driven by local food shortages. Interestingly, food aid from some of the largest donors is the least responsive to production shocks in recipient countries. Second, we show that U.S. food aid is partly driven by domestic production surpluses, whereas former colonial ties are an important determinant for European countries. Third, amongst recipients, former colonial ties are especially important for African countries. Finally, aid flows to countries with former colonial ties are less responsive to recipient production, especially for African countries.

[Adapted from Ratnakar Adhikari’s article in Trade Insight magazine, vol.6, No.3-4, 2010. p.25-28]

The history of South-South development cooperation (SSDC) is nearly as old as the history of North-South development aid. However, this issue has come under the scanner of development practitioners only in the recent past due primarily to their increased significance in the backdrop of the global financial crisis, which was feared to result in a global resource squeeze. Although SSDC is not likely to replace traditional development cooperation, it is likely to be of tremendous significance in the days to come—thanks mainly, but not exclusively, to the growing economic prowess of advanced developing countries.

Growing salience

The evolving dynamics of cooperation among Southern countries and its potential to contribute to global prosperity constitute probably the single major reason to discuss the growing salience SSDC. For the least-developed countries (LDCs), handicapped by several supply-side constraints to take advantage of the growing global economic integration, SSDC offers an opportunity over and above traditional official development assistance (ODA). Although the burgeoning SSDC is often ascribed only to the growing economic clout of the emerging economies, there are several factors that have contributed to this phenomenon, some of which are discussed below.

First, SSDC should be seen in a broader context of the increased economic integration among developing countries. While the LDCs were largely reliant on developed countries for trade in the past, there seems to be a trend towards increased flow of South-South trade. For example, South-South trade has nearly doubled between 1995 and 2008 to reach nearly 20 percent.1 Similarly, South-South flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) has reached 16 percent, up from 12 percent in the 1990s.

Second, there is an expectation among the partner LDCs to learn from the economic and development success of Southern donors. At a general level, the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), for example, argues that many Southern donors have come up with successful development models or practices, which can be more appropriately replicated in other developing countries.2

Third, due to the inability of the traditional donors to live up to their ODA promises, the LDCs have found it necessary to tap into the funding offered by Southern donors. The LDCs find such assistance more practical and efficient in terms of disbursement causing fewer significant delays compared to that of traditional donors.3 SSDC is also presumed to be based on solidarity,4 and the principle of equality, as opposed to clientalism that characterizes traditional aid relationship. Some Southern donors are found to be more flexible and responsive to the national priorities of partner countries.5

Current status of SSDC

The Reality of Aid Management Committee has compiled the disbursement data of South-South ODA from various sources for 2008 (Table). It is, however, necessary to note that unlike North-South ODA data, which are prepared by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), due to several difficulties associated with the collection of South-South ODA data,7 the data presented below should not be considered as authoritative.

| Disbursement of selected South-South ODA flows, 2008 (US$ million) | |||

| South-South donor | Amount | % of GNI | % of total South-South ODA |

| Saudi Arabia | 5,564 | 1.5 | 40 |

| Venezuela | 1,166–2,500 | 0.71–1.52 | 18 |

| China | 1,500–2,000 | 0.96–0.08 | 14.4 |

| South Korea | 802 | 0.09 | 5.8 |

| Turkey | 780 | 0.11 | 5.6 |

| India | 569 | 0.05 | 4.1 |

| Taiwan | 435 | 0.11 | 3.1 |

| Brazil | 356 | 0.04 | 2.6 |

| Kuwait | 283 | 0.18 | 2 |

| South Africa | 194 | 0.07 | 1.4 |

| Thailand | 178 | 0.07 | 1.3 |

| Israel | 138 | 0.07 | 1 |

| United Arab Emirates | 88 | … | 0.6 |

| Malaysia | 16 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

| Argentina | 5–10 | 0.003–0.005 | 0.07 |

| Chile | 2–3 | 0.003 | 0.02 |

Source: Adapted from Reality of Aid Management Committee. 2010. A Challenge to the Aid System? Special Report on South-South-South Cooperation:South Cooperation. Manila: IBON Books.

South-South ODA from the top 16 countries for which data were available reached close to US$14 billion. Four major donors, namely Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, China and India, collectively account for over 76 percent. Saudi Arabia, a major aid donor since 1973 as measured by the ODA-gross national income (GNI) ratio, provided more than US$5.5 billion in development assistance representing 1.5 percent of its GNI. This figure is 40 percent of the total development assistance provided by the top 16 developing-country donors.

Although most assistance provided by the major South-South donors is in the form of project aid, there are also components of technical cooperation, budget support and humanitarian assistance. Among the top four donors, Venezuela’s case is unique in the sense that its oil deals assume the form of balance-of-payments (BoP) support.8 However, like Northern donors, the motives behind South-South ODA are not entirely altruistic.

Saudi Arabia’s official aid policy has an explicit objective of promoting its non-oil exports. Chinese commercial interests are mainly reflected in the desire to obtain an uninterrupted supply of energy and raw material resources from partner countries. For example, when providing aid to Angola, China does not directly provide funds to the government but mandates a Chinese construction company to build infrastructure and expects the government of Angola to provide Chinese companies operating in the field of oil the right to extract oil through the acquisition of equity stakes in a national oil company or through the acquisition of licences for production.9 Similarly, India’s ODA —particularly for the construction of infrastructure—mainly to Bhutan and to a lesser extent to Nepal is aimed at securing hydroelectricity and energy for itself.10 India’s pledge of US$500 million in concessional credit facilities to resource-rich African LDCs (Burkina Faso, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Cost, Mail and Senegal) and one developing country (Ghana) shows Indian tendency to follow the Chinese model for resource extraction from Africa.

Similarly, geopolitical interests are reflected in the choice of partner countries. Saudi aid is mostly provided to Arab countries. Venezuelan aid mainly goes to Latin American and Caribbean countries. Indian assistance is targeted predominantly at South Asian countries with Bhutan receiving 46 percent of total aid, and the Maldives and Afghanistan receiving 19 and 16 percent respectively. However, China’s aid is much more diversified, with Asian countries receiving 40 percent, followed by Africa (25 percent), and Latin and Central America (13 percent).11

Saudi Arabia’s support predominantly to the Muslim countries in the Arab region (including relatively better-off countries such as Turkey and Egypt, themselves donors, and Morocco compared to poor countries in sub-Saharan Africa) and two Muslim countries in South Asia (Bangladesh and Pakistan and not to Nepal and Bhutan, despite the latter being LDCs) shows the influence of religious and cultural factors in its country-selection process.12 Similarly, Brazilian technical cooperation programmes in Portuguese-speaking African countries (77 percent of its total assistance to Africa) and East Timor (96 percent of its total Asian assistance) shows the significance of the language factor.13

Solidarity interest, together with geopolitical interest, is seen dominant in the ODA provided by Venezuela, a founder member of Alternativa Bolivariana para las Americas (ALBA). This initiative focuses on integration among Latin American countries, through a “socially-oriented trade bloc”14 proposed as an alternative to the Free Trade Area of the Americas.

Challenges facing LDCs

While the growing importance of SSDC is a reality the LDCs cannot ignore, SSDC is not free of all the problems that have dogged the issue of development aid in general, and also presents additional challenges.

Tied aid

While traditional donors have made significant progress in untying aid, assistance under SSDC, particularly by the major donors, is primarily tied.15 For example, in the case of Chinese aid to Africa, 70 percent of the infrastructure construction projects have to be awarded to “approved”, mostly state-owned, Chinese companies. Although the remaining 30 percent contract can be awarded to local companies, they too are mostly established in joint-venture arrangements with Chinese companies.16 Even the labour component of the contracts is fulfilled by imported Chinese workers in countries as varied as Mauritius, Nepal and Sri Lanka.17

Similarly, at least 85 percent of the value of South-South concessional loans granted by India under its India Development Initiative was meant to be tied to Indian procurement.18 Examples include a US$40 million credit line for railway reconstruction in Angola, and a donation to Sierra Leone of US$800,000 for the construction of 400 barracks.19 Similarly, Venezuelan BoP support is primarily tied to oil imports, and Korean bilateral aid is also predominantly tied.20

Lack of transparency

There is a serious lack of accessible and comprehensive information on South-South ODA. This could be because even the major Southern donors do not have central coordinating agencies to manage and monitor development assistance at the national level. The problem is further compounded by the deliberate secrecy on both sides of the partnership.21 This is particularly so in the case of Arab donors and China. For example, sloppy distinctions between Chinese investment, loan and aid on the one hand, and "proposed", "agreed", "under construction", "concluded", "realized", "(un)confirmed" nature of supports on the other, provided by China under China-Africa technical cooperation make it almost impossible to know the exact nature and magnitude of support extended by China.22

The result is, it is difficult to collect data and make an informed analysis for policy purposes. A more maligned outcome is the difficulty in establishing which Southern donor is funding which institution in which country for what purpose. There is also the question of debt-sustainability since it is difficult to ascertain how much the partner country owes to its donors. The democratic ownership of SSDC is also under question, because such aid tends to be mostly government-to-government with little involvement of the parliament and civil society.23

Limited ownership

Although SSDC, in theory, tends to promote country ownership at the programme and project development level, it is reported that some Southern donors have preferred to fund the construction of a stadium as opposed to the priority identified by partner countries for the construction of roads. Similarly, the focus of infrastructure development on resource extraction, rather than on building productive capacity at the local level, limited use of local inputs in the process of project implementation, and the lack of a clear mechanism for technology transfer leave much to be desired.

Inadequate monitoring and evaluation

There is little public information available on the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) procedures of Southern donors.However, country experiences suggest that these donors conduct significantly fewer missions to review project progress than Northern donors. Overall, M&E systems of Southern donors seem to be largely concerned with timely project completion.24

Unlike traditional donors, which are bound by the in-built DAC peer review mechanism with a strong M&E component, Southern donors are not subjected to any such M&E mechanism. Although proposals have been made by the Group of 77 countries and non-governmental organizations to strengthen the UN Development Co-operation Forum (DCF) to serve as an alternate platform for aid negotiations to DAC, there is limited progress in this direction, primarily due to the skepticism of the traditional donors and capacity of the under-resourced UN to handle these responsibilities.25

Non-applicability of Paris Declaration

In order to enhance the effectiveness of development aid in general, traditional donors as well as partner countries signed on to the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (in 2005), which defines a number of commitments, and a set of indicators to measure progress towards 2010. The Declaration is based on five common sense tenets of ownership, alignment, harmonization, result management and mutual accountability.

However, the Declaration is not applicable to SSDC, except for a few Southern donors such as Korea and Turkey which have signed on to it in view of their impending admission to the DAC. Although the Accra Agenda for Action, issued in September 2008, recognizes the important role of SSDC in international development cooperation and considers it as a valuable complement to North-South cooperation, it does not exhort Southern donors to become parties to the Paris Declaration. This effectively means that Southern donors are not even obliged to make efforts to overcome the challenges facing traditional development cooperation.

Issues for UNLDC IV

Since development assistance is a core development agenda for the LDCs, the issue of SSDC needs to be extensively deliberated upon both in the run-up to the Fourth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries as well as during the conference itself. It is indeed surprising that this issue has not so far entered the discussions in the run-up to event. Therefore, based on the challenges discussed above, the following issues are worth taking up.

First, as tied aid does not contribute much to the development of the local economy and local human capital and prevents the partner country from sourcing inputs from competitively priced sources, a target—possibly of 2021—should be set, for the gradual untying of aid by Southern donors.

Second, although project financing has been the preferred mode of funding for Southern donors, they should gradually move towards a sector-wide approach and eventually towards budgetary support.

Third, SSDC should be brought under some global process of discussions, negotiations, target setting, coordination, reporting, and monitoring and evaluation. While there is a near consensus on the need for the same, there is a considerable disagreement between developed countries and developing countries on which platform should be used. As a compromise, it is proposed that a two-track mechanism be adopted whereby DAC would continue to coordinate traditional ODA matters and DCF would be assigned the full responsibility of coordinating issues relating to South-South ODA. DCF should begin its activities by preparing a framework like the Paris Declaration for coordinating and monitoring SSDC

Fourth, partner-country governments, on their part, should commit to use the resources received from Southern donors in a transparent manner and involve all the major stakeholders, including parliament, the private sector and civil society, in the process of programme design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation.

Notes

1 Onguglo, Bonapas. 2010. A More Dynamic & Transformative South–South Trade. International Trade Forum - Issue 2/2010. http://www.tradeforum.org, accessed 04.11.10.

2 ECOSOC. 2008. Trends in South-South and Triangular Development Cooperation. Background Study for the Development Cooperation Forum. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Council.

3 ibid, p 29.

4 See Reality of Aid Management Committee. 2010. South-South Cooperation: A Challenge to the Aid System? Special Report on South-South Cooperation 2010 of the Reality of Aid. Manila: IBON Books, pp. 1–2.

5 For example, Venezuela, Arab donors and India have provided flexible budget and BoP support to select partner countries. (Note 2, p 28).

6 ECOSOC. 2008. Note 2.

7 ECOSOC. 2009. South-South and Triangular Cooperation: Improving Information and Data. 4 November. New York: Office for ECOSOC Support and Coordination Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

8 Note 4, p 9.

9 Paulo, Sebastian and Helmut Reisen. 2010. Eastern Donors and Western Soft Law: Towards a DAC Donor Peer Review of China and India? Development Policy Review 28 (5): 535–552, p 538.

10 Reality of Aid Management Committee. 2010. p 12. Note 2.

11 Note 4, p 9.

12 Note 4, p 11.

13 Note 2, p 18.

14 Note 2, p 20.

15 Note 2, p 30.

16 Note 4.

17 The example of Chinese workers’ involvement in Mauritius is provided by Paulo and Reisen. 2010: 538. (Note 9). The example of Nepal and Sri Lanka is based on the author’s personal observation. See also Note 2, p 32.

18 Bijoy, C.R. 2010. India: Transiting to a Global Donor. In The Reality of Aid Management Committee. 2010. (Note 4).

19 ibid.

20 Note 2, p 29.

21 Note 4, p15

22 Note 9, p 538.

23 Note 4, p 16.

24 Note 2.

25 Note 9, p 549.

A new report by UNRISD (Combating Poverty and Inequality: Structural Change, Social Policies and Politics) explores the causes, dynamics and persistence of poverty; examines what works and what has gone wrong in international policy thinking and practice; and lays out a range of policies and institutional measures that countries can adopt to alleviate poverty. The main point of the report is that the existing approaches to poverty often ignore its root causes, and do not follow through the causal sequence. The report argues, “persistent poverty in some regions, and growing inequalities worldwide, are stark reminders that economic globalization and liberalization have not created an environment conducive to sustainable and equitable social development.”

It advocates a pattern of growth and structural change that can generate and sustain jobs that are adequately remunerated and accessible to all-- regardless of income or class status, gender, ethnicity or location. It calls for comprehensive social policies that are grounded in universal rights and that support structural change, social cohesion and democratic politics.

It argues that civic rights, activism and political arrangements should be in place to ensure that states are responsive to the needs of citizens and that the poor have influence over the policies that are intended for their welfare.

Basically, it is criticizing the poverty reduction approaches led by the IMF and the WB (Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs)), some of the social protection programs, and the MDGs. It assets that these approaches push for “discrete social policies that are often weakly related to a country’s system of production and macroeconomic policies.”

Major points about poverty and inequality and policy recommendations:

Although there are specific recommendations and discussions, some of the points are as general (and vague) as they can get. These are easier said than done. There are contradictions as well. For instance, periodic change in power has been seen as one of the political tools to reduce poverty. It assumes that the change in power would bring more pro-poor poverty reduction policies. However, without change in power, there have been so many instances of drastic change in poverty levels (e.g. Japan ruled by LDP for over fifty years, China under one-party rule and Vietnam under similar condition, Singapore evolving similarly after the British left them in the 1970s). Implementing all the poverty-reducing policy recommendations of this report is simply out of the reach of the developing countries due to institutional and resource constraints. Not a really enlightening report as most of the points were already floated out in other papers. What could have been interesting is the near-precise process of attaining the goals set in the policy recommendations. This is missing in literature on poverty and inequality. This report also misses this crucial aspect.

The latest UNCTAD publication Creative Economy Report 2010 argues that the demand for some "creative industry" products -- particularly those which are domestically consumed, such as videos, music, video games, and new formats for TV programmes -- remained stable during the global recession, and this economic sector, especially if supported by enlightened government policies, may help national economies, including those of developing countries, to recover from the downturn. Here is UNCTAD’s database on creative industries.

Global exports of creative goods and services -- products such as arts and crafts, audiovisuals, books, design work, films, music, new media, printed media, visual and performing arts, and creative services -- more than doubled between 2002 and 2008, the report notes. The total value of these exports reached US $592 billion in 2008, and the growth rate of the industry over that six-year period averaged 14%.

The report says that the creative industries hold great potential for developing countries seeking to diversify their economies and participate in one of the most dynamic sectors of world commerce. The global market already had been boosted by increases in South-South trade in creative products before the recession set it in. The South’s exports of creative goods to the world reached $176 billion in 2008, or 43% of total creative-industries trade.

One of the key recommendations of the report is that developing countries should include creative goods in their lists of products, and should conclude their negotiations under the Global System of Trade Preferences so that they give more impetus to the expansion of South-South trade in this sector. The rate of growth in such trade of creative goods – from $7.8 billion in 2002 to $21 billion in 2008 – is an opportunity that should be fully realized, the report says.

South Asia and creative industries’ goods trade

In South Asia, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal have less emphasis on creative-industry development, but craft industries, furniture making and handloom industries have traditionally been widespread.

In total, Nepal’s exports of creative industries’ goods were US$14.52 million and imports from South Asia were US$37.79 million in 2003. The figures are of the latest year available. Nepal exported US$ 79.50 million and imported US$ 58.75 million worth of creative industries’ goods from the world. So, in terms of trade of creative industries’ goods, Nepal has trade surplus with the world but a deficit with South Asia.

Trade of creative industries’ goods within South Asia was US$ 275.59 million of exports and US$ 255.68 million of imports in 2008. The corresponding figures for 2002 were US$ 19.98 million and US$ 28.30 million, respectively.

South Asia’s exports of creative industries’ goods to the world were US$ 11160.56 and imports were US$3481.86 million in 2008. The corresponding figures for 2002 were US$250.28 million and US$ 430.92 million, respectively. The 2008 figures represent 2.74 percent and 0.83 percent of South Asia’s exports and imports as a share of world export and imports.

Creativity, knowledge and access to information are increasingly recognized as powerful engines driving economic growth and promoting development in a globalizing world.