On 29 April 2022, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) estimated that Nepal’s economy will likely grow by 5.8% in FY2022, up from 4.2% growth in FY2021 (this is revised estimate). This projection is a bit more optimistic than what most have expected but is still lower than the government’s 6.5% growth target. The gradual resumption of economic activities, including tourism and hydroelectricity generation, with no disruption caused by the pandemic and the expectation of local elections related spending have driven the optimistic projection. FYI, fiscal year (FY) starts from mid-July of t-1 year and ends on mid-July of t year (for instance, FY2022 refers to the period between mid-July 2021 and mid-July 2022).

FY2021 performance (revised estimate)

GDP in FY2021 grew by 4.2%, up from a contraction of 2.4% in FY2020, thanks to a combination of base effect and resumption of economic activities as the pandemic related restrictions eased. Base effect refers to the tendency of achieving an arithmetically high rate of growth when starting from a very low base.

Agricultural output is estimated to have grown by 2.8% in FY2021 owning to favorable monsoon and a surge in agricultural workers (lockdowns forced reverse migration and contributed to more migrant workers’ engagement in agricultural work) that had a positive effect on paddy output. Industrial output grew by 4.2% from a contraction of 4% in FY2020 as mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and construction activities picked up pace after contraction in FY2020. Services output grew by 4.2% from a contraction of 4.5% in FY2020 as wholesale and retail trade, travel and tourism, financial and insurance and healthcare activities gradually recovered from severe slump in the previous year.

FY2022 performance (provisional estimate)

The CBS projects GDP to grow by 5.8% in FY2022, up from 4.2% revised estimate for FY2021, thanks to a surge in industrial output driven by hydroelectricity generation and services output driven by travel and tourism activities. Overall, while public investment contracted, private investment and consumption increased.

Agricultural sector will likely contribute 0.7 percentage points, industrial sector 1.6 percentage points, and services sector 3.2 percentage points to the overall projected GVA growth (basic prices) of 5.5%. GVA at basic prices + taxes less subsides = GDP at market prices.

The sectors with highest growth include electricity, gas and related utility (36.7%), followed by accommodation and food service activities (11.4%), construction (9.5%), wholesale and retail trade (9.1%), mining and quarrying (8.2%), and human health and social work activities (6.9%) among others.

The estimates are based on data and information up to the first nine months of FY2022 (mid-July 2021 to mid-April 2022) and assumption of normal economic activity during the rest of the fiscal year (mid-April 2022 to mid-July 2022).

Agricultural output is projected to grow at 2.3%, up from 2.8% in FY2021, largely due to unfavorable monsoon, which affected paddy output. Paddy harvest was affected by unseasonal torrential rain in October that also damaged physical infrastructure and killed over 100 people. The Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development said that an estimated 424,113 tonnes of paddy on 111,609 hectares had been destroyed.

Industrial output is projected to increase by 10.2%, up from 4.5% in the previous year, on the back of a substantial increase in additional hydroelectricity generation. Mining and quarrying activities grew by 8.2%, up from 7.5% in FY2021, as residential housing and real estate and development work including hydropower, picked up pace. Mining and quarrying of stones, sand, soil and concrete also get affected by construction sector. Construction activities grew by 9.5%, up from 5.2% in FY2021, as supplies of construction materials normalized (both import and domestic supply), and households, commercial and infrastructure projects picked up pace. It was aided by highly accommodative monetary policy as credit growth shot up relative to deposit growth. A part of refinancing and business continuity loans, which were rolled out as a part of relief measures to help struggling businesses, also made its way to housing and real estate sectors.

Manufacturing grew by 6.1%, up from 4.1% in FY2021, as industrial capacity utilization improved from resumption of economic activities. It has been suffering from low private sector investment, and loss of both domestic and external markets due to eroding cost and quality competitiveness. A stable supply of electricity and improved industrial relations were not sufficient to markedly boost manufacturing output as expected. Meanwhile, the addition of 456MW of electricity from Upper Tamakoshi hydroelectricity project sharply increased electricity output, propelling its growth to 36.7% from just 2.6% in FY2021. However, this has not been sufficient to bridge the electricity demand-supply gap during the dry season. The NEA recently was compelled to introduce loadshedding for industries due to large demand-supply gap and lower imports from India. This could weigh in on the sector’s eventual gross value added output.

Services output is projected to grow by 5.9%, up from 4.2% in FY2021, thanks to pick up in travel and tourism, and wholesale and retail trade activities. The latter is expected to grow by 9.1%, up from 5.7% in FY2021 as supplies disruptions eased and consumer demand picked up pace, which was also aided by loose monetary and fiscal policies. Surge in import of agricultural and industrial goods in the first two quarters aided. Due to the deterioration of external sector stability and a decline in forex reserves, the government and the central bank started tightening import financing and, in some cases, outright ban on imports. This will affect the sector’s growth in the last quarter of FY2022. Transportation and storage activities are expected to grow by 4.5%, almost at the same rate as in the previous year, despite loosening of international and domestic travel restriction. However, travel is still expensive, which is exacerbated by the increase in fuel prices triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Accommodation and food service activities are expected keep growing at a robust pace— 11.4%, up from 10.7% in FY2021—, thanks to a strong pick up in domestic travel and tourism.

Information and communication are expected to grow by 3.6%, up from 1.8% in FY2021. Financial intermediation is projected to grow by 6.1%, higher than 4.0% in FY2021, reflecting improved income of NRB, BFIs, insurance board and companies, securities board, social security fund, EPF and CIF. Real estate activities are expected to increase by 3.8%, up from 2.4% in FY2021, as sale, purchase, lease and other activities related to real estate picked up pace. The proposed local elections related spending on security and public administration is expected to increase public administration and defense activities by 4.4% from 2.3% in FY2021. Healthcare related demand continues to remain strong, keeping its growth rate above 5% since FY2017.

Agriculture, industry and services sectors accounted for 29.4%, 16.3% and 54.4% of GDP in FY2022.

On the expenditure side, consumption is expected to increase by 5.4%, up from 3.7% in FY2021. While public grows fixed investment contracted by 6%, private fixed investment grew by 8.8%. They grew at 22.2% and 5.6%, respectively in FY2021. Net exports are expected to grow at 12.1%, thanks to exports growth being much higher than imports growth. In fact, imports are expected to grow at a lower rate in FY2022 than in FY2021 as the government and the central bank tightened import financing and at times imposed outright import ban.

Here are quick takeaways from the latest GDP projection.

First, it may be a bit optimistic projection even after accounting for local elections related spending and normal economic activity in the last quarter of FY2022. The remains three months will be anything but normal in terms of economic activities. Import restrictions, deceleration of official remittance inflows, depreciation of Nepali rupee, rising energy and commodity prices, restrain in government recurrent spending to some extent, and the scheduled electricity blackouts for industries, among others, will depress output and aggregate demand. When revised or actual figures are released, it might be adjusted to around 4.5-5.0%.

Second, the outlook for FY2023 is not rosy.

- First, despite the projection of above average monsoon (June to September 2022), the uncertainty over supply of other inputs (chemical fertilizers, access to seeds, access to finance, etc) dims agricultural sector’s growth prospects. Specifically, the shortage of chemical fertilizers will be painful because a good monsoon may increase the area of paddy plantation, but it will not necessarily increase output per hectare of land. Chemical fertilizers are key ingredients to boosting total output and output per hectare of land (productivity).

- Second, the slowdown in residential and commercial real estate and housing will affect mining and quarrying, and construction activities. The surge in real estate and housing prices, fueled by easy financing even during the pandemic, has started to taper off as banks and financial institutions tighten lending.

- Third, with no drastic addition of hydroelectricity to the national grid and the scheduled electricity blackouts for industries, utility and manufacturing activities may not pick up pace. In fact, industrial capacity utilization may decrease because of both high fuel prices and shortage of electricity. This will be exacerbated by the shortage of imported industrial inputs (industrial raw materials and intermediate goods) either due to outright ban on import of certain goods or tight foreign currency financing to slowdown imports. Factories are enduring up to 14 hours of blackouts due to low generation during dry season and expensive import price of electricity through the power exchange from India. Between 2007 and 2017, the country is estimated to have lost over 6% of GDP due to loadshedding.

- Fourth, high energy and fuel prices will also affect services sector activities because a rise in cost of production and inflation will dampen consumer demand. For instance, wholesale and retail trade, and transportation and storage will get affected by both import restrictions and high energy and commodity prices, especially through lower consumer demand as real purchasing power weakens. These two sectors account for about 21% of GDP. Similarly, international and domestic travel, and accommodation and food services will remain expensive, restraining these sectors from sustained recovery.

Against the backdrop of dampening consumer demand due to high cost, deceleration of remittances and tighter monetary policy, slight pick up in travel and tourism and federal and provincial elections related spending may not be enough to sustain GDP growth above 5%. A sustained V-shaped recovery looks less likely.

Third, external sector stress is building up. Since import of petroleum fuel constitutes about 15% of total imports, the import bill is rising sharply. Import demand for petroleum products is relatively inelastic given the lack of immediate substitutes. The import bill of petroleum products in the first eight months of this fiscal year 2021/22 is already higher than the total import of petroleum products for the whole of 2019/20. Note that rise in petroleum fuel prices passes through to other goods as well because it is used in production process and transportation of the goods. Hence, import bill of other goods such as vehicles, machinery and agricultural items is also increasing. Import bill of wheat, rice, crude soya bean oil and edible oil has also increased. Despite gradual recovery in exports, the large import bill has increased import bill by 34.5% in the first eight months of this fiscal. This combined with the deceleration of remittance inflows amidst modest services recovery led by tourism sector widened current account deficit by around 200% in the first eight months of this fiscal. Consequently, balance of payments remains in negative territory with a depletion of foreign exchange reserves which are sufficient to cover 6.7 months of import of goods and services. It was 11.3 months in mid-March 2021. The rapid rise in energy and food prices poses a significant risk to external sector stability. Restricting non-essential imports is a band-aid solution to the structural issue.

Fourth, the recent deterioration of macroeconomic indicators precedes the highly accommodative fiscal and monetary policies after the pandemic started. The vulnerabilities were building up, but the accommodative policies simply masked them. As exogenous forces triggered external sector stress amplify and pandemic related support measures are gradually withdrawn, the vulnerabilities not only unmasking but also exacerbating (stagnating revenue but rising expenditure, low capital budge absorption capacity, asset liability mismatch, evergreening and non-performing loans, low exports but rising imports, sectoral bubbles, etc). For instance, fiscal profligacy led to higher deficit especially after federal, provincial, and local elections in FY2017. Total federal expenditure increased by an average 19.3% between FY2017 and FY2022 (includes budget estimates), but total federal receipts increased by only 14.2%. Consequently, average fiscal deficit was above 5% of GDP. Fiscal balance was either under 3% of deficit or outright surplus (due to low capital spending) before FY2017. This large and growing fiscal deficit increased public demand (consumption and investment) and boosted imports. Meantime, public debt also started rising rapidly. It was just 22.7% of GDP in FY2017 but rose to 40.6% of GDP by FY2021. With this also increased debt servicing costs.

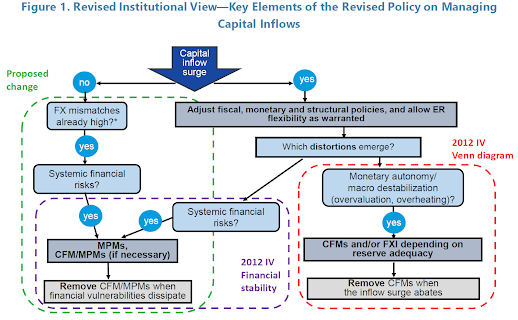

Similarly, the loose monetary policy and a weak oversight encouraged higher credit growth relative to deposit growth. It was fueled by remittance inflows as well. For instance, the average annual growth rate of deposit over FY2017-FY2021 was 18.3% compared to credit (loans and advances) growth of 21.2%. The weak banking sector oversight fueled real estate, housing, and stock markets bubbles, and encouraged imports. The increase in imports, which increased revenue that incentivized the government to ignore early warning signs of vulnerabilities build up (45% of revenue is import based), started draining foreign exchange reserves after the pandemic at a pace that is perceived to be unsustainable unless corrective actions are taken. During the first eight months of FY2022, foreign exchange reserves were sufficient to cover 6.7 months of import of goods and services. It was 11.3 month in mid-March 2021. Given the currency peg with the Indian rupee, vulnerability to natural disasters and the need for an additional buffer for remittances and tourism-related vulnerabilities, the optimal level of reserves is estimated to be 5.5 months of prospective import of goods and services. The country earns foreign exchange reserves mainly through exports, travel and tourism, investment income, remittances, grants and loans, and foreign direct investment— all of which are below the pre-pandemic level. So, the raft of measures to discourage imports recently in response to the fast-depleting foreign exchange reserves is just a band-aid solution to structural issues. The solution should start with tightening of monetary policy and measures to rein in government spending.

Fifth, the rising inflation— thanks primarily due to high prices of petroleum fuel, LNG, and imported goods— will have a disproportionate effect on the most vulnerable people. The lowest income and poorest households are hit the hardest by increase in fuel and food prices because it constitutes about 65% of their consumption expenditure. For the richest households in the consumption quintile, it is just 34.6%

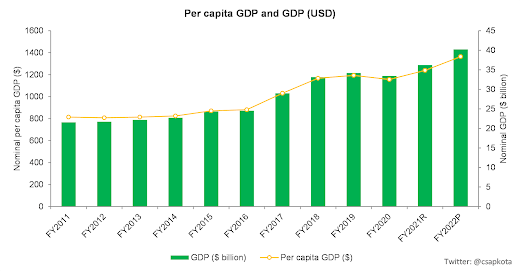

Sixth, the size of Nepali economy is estimated at US$40.2 billion. Per capita GDP and per capita GNI are estimated at $1364 and $1380, respectively. GNDI (GNI + net current transfers incl remittances) is estimated to reach 123.3% of GDP. Gross domestic savings (GDP – consumption) is around 9.3% of GDP, reflecting high level of consumption. The country’s population in FY2022 is estimated to be 29.5 million.