In its 2022 Article IV consultation report on India, the IMF noted that the economy rebounded strongly from the pandemic-related downturn, supported by fiscal policy targeted at vulnerable groups and to mitigate the economic impact of commodity price increases. Front-loaded monetary policy tightening is addressing elevated inflation and a robust public digital infrastructure is facilitating innovation, productivity improvements and access to services.

However, the India economy is facing new headwinds, including the adverse effect of climate change. These include high fiscal deficit that requires consolidation anchored on stronger revenue mobilization and spending efficiency; monetary policy tightening to rein in inflation and financial sector vulnerabilities; and financing and technology transfer to move to a carbon-neutral economy. This blog post includes key highlights from the report.

Recent developments

The economy benefited from broad-based recovery from the deep pandemic-related downturn. Real GDP grew by 8.7% in FY2022. All sectors recovered to pre-pandemic levels by end-FY2021/22 except for contact-intensive services, which remained 11% below FY2019/20 levels.

Due to growing domestic demand, commodity and food price shocks, and supply chain disruptions, inflation has been at or above the RBI’s inflation band of 4±2% since January 2022. The report notes that long-term inflation expectations remain relatively well anchored, but the risk of second-round effects from fuel and commodity price shocks remains high.

Credit growth increased following relatively subdued growth over the past two years. Non-food bank credit growth was driven by stronger credit growth by private banks, mostly to MSMEs in the industry sector. However, credit gap (credit to GDP gap) remains negative, i.e. credit-to-GDP ratio remains below its long-term trend.

The external position in FY2022 was considered broadly in line with that implied by medium-term fundamentals and desirable policies (level of per capita income, favorable growth prospects, demographic trends, and development needs). Current account surpluses and large capital inflows boosted international reserves during the pandemic. The IMF assessed current account gap at 1% of GDP after accounting for transitory impacts of the COVID-19 shock. Current account deficit in FY2022 was 1.2% of GDP, reflecting recovering domestic demand and rising commodity prices. The widening current account deficit and portfolio investment outflows have depleted foreign exchange reserves in FY2023. External shocks such as global financial tightening and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and recovering domestic demand have put pressure on the exchange rate. Reserves are enough to cover around 7 months of prospective imports.

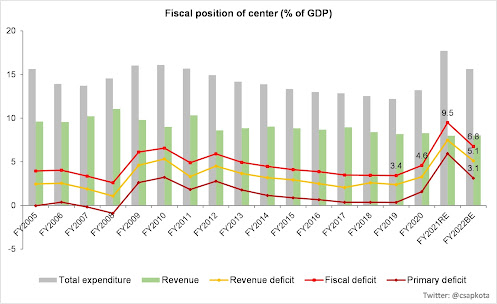

General government fiscal deficit is estimated to decrease to 9.9% of GDP in FY2023 from 10% of GDP in the previous fiscal. Central government fiscal deficit declined to 6.7% of GDP in FY2022 (in its definition of central government deficit, the IMF also includes NSSF loans to central government PSUs and fully serviced bonds). The phasing out of some pandemic-related expenditures contributed to 1% of GDP reduction in spending. Buoyant GST and income tax revenues, thanks to improvements in tax administration and additional taxes on domestic crude oil production and fuel exports, helped boost revenue. The state government’s deficit is estimated to decline close to the medium-term target of 3% of state-level GDP, but variations in fiscal performance persist.

The pandemic-related disruptions reduced access to education and trainings, adversely impacting human capital accumulation. Most affected were vulnerable groups, including females, youth, less skilled and educated, and daily wage and migrant workers.

Economic outlook

Growth is projected to moderate amid higher oil prices, weaker external demand, and tighter financial conditions. The IMF projected GDP growth at 6.8% in FY2023 and 6.1% in FY2024. Growth is projected at around 6% over the medium-term.

General government fiscal deficit is projected to moderate but will remain high: 9.9% of GDP in FY2023, 9% of GDP in FY2024 and then around 7-8% of GDP over the medium-term.

Inflation is projected to moderate to 6.9% in FY2023 as core inflation remains sticky and near-term uncertainties in food prices and input costs affect prices. Inflation is projected to return to the tolerable band over the medium-term.

Current account deficit is projected to increase to 3.5% of GDP in FY2023 owing to higher commodity prices and import demand, and will decline to about 2.5% of GDP over the medium-term.

Foreign exchange reserves are projected to cover about 6.5 months of imports over the medium-term. Net FDI inflows are estimated to be about 1.4% of GDP.

Risks to outlook: Uncertainty about the economic outlook is considered high and risk tilted to the downside. A materialization of these risks would worsen the economic outlook (lower growth and trade).

External risks include a sharp global growth slowdown (affects India through trade and financial channels), and intensification of spillovers from the Russian invasion of Ukraine combined with supply and demand shocks in the global food and energy markets. These can worsen inflation and de-anchor inflation expectations. Over the medium-term, broadening of conflicts and reduced international cooperation can disrupt trade, increase volatility of commodity price, and fragment technological and payments systems.

Domestic risks include rising inflation impacting vulnerable groups, emergence of more contagious COVID-19 variants, tighter financial conditions (weaken asset quality and result in financial sector stress), high financing costs due to weakening of fiscal position, climate change.

However, upside risks include a resolution of the war in Ukraine and de-escalation of geopolitical tensions (will boost international cooperation, moderate commodity price volatility, and promote trade and growth). Also, successful implementation of structural reforms and greater than expected dividends from ongoing digital advances could increase medium-term growth potential.

Fiscal policy: India’s fiscal space is at risk and debt sustainability risks have increased. The government will need to improve targeting to lower public spending. For instance, the reduction in fuel excise taxes and additional fertilizer subsidies are not well targeted. Revenue have been improving due to buoyant GST and income tax revenues. High debt levels (84% of GDP in FY2022) and substantial gross financing needs (15% of GDP) due to higher effective interest rates together with monetary policy tightening have increased debt sustainability risks. These risks are somewhat mitigated as the bulk of public debt are fixed-rate instruments denominated in domestic currency and predominantly held by residents per regulatory requirements. DSA shows that debt dynamics remain favorable in the medium-term and support a sustainable debt path.

The government has targeted 4.5% of GDP central government deficit, implying a general government deficit of 7.5% of GDP (down from 9.9% of GDP in FY2023). The IMF recommends a clearly communicated medium-term fiscal consolidation plan to enhance policy space and facilitate private sector-led growth. It will also reduce uncertainty, lower risk premia, and help to maintain price stability.

Fiscal consolidation should be facilitated by stronger revenue mobilization and improving expenditure efficiency. General government primary consolidation of around 1% of GDP and debt of around 80% of GDP by FY2028 could be targeted.

Expenditure efficiency is possible through better targeting of subsidies, greater utilization of the existing social support infrastructure (DBT) to reduce leakages, rationalization of central schemes, reforming electricity tariffs and improving the financial viability of electricity distribution companies.

Revenue measures can include reversing the fuel excise tax cuts, further broadening the corporate and personal income tax bases, simplifying the goods and services tax (GST) rate structure, rationalizing the items subject to preferential GST treatment, and continued improvements in tax administration, in line with international good practice. These measures would help narrow India’s tax gap, estimated at around 5% of GDP. Asset monetization and privatization agenda could generate additional receipts.

Fiscal transparency will improve PFM. For instance, recognizing previously off-budget expenditure at the center and state level has improved transparency. Digital solutions have helped streamline PFM processes, advancing transparency and governance, including through e-procurement, faceless income tax assessments and the recent rollout of e-bills. Integrated Government Financial Management System along with a dedicated platform for central, state, and local governments to share fiscal information will support timely production of consolidated fiscal reports and identification of fiscal risks at the subnational level.